Flame Retardants

|

WARNING! Sewage sludge is toxic. Food should not be grown in "biosolids." Join the Food Rights Network. |

|

This article is part of the Tobacco portal on Sourcewatch funded from 2006 - 2009 by the American Legacy Foundation. |

Flame Retardants refer to over 175 different chemicals used to inhibit ignition of combustible organic materials. These chemicals are classified into groups including halogenated organic (typically brominated or chlorinated), phosphorus-containing, nitrogen-containing, and inorganic flame retardants.[1] The more than 75 chemicals included in the category of brominated flame retardants (BFRs) are commonly used because they are effective and cheap. However, some are also dangerous to human health.

Both Tris and polybrominated biphenyls (PBBs) were proven harmful and thought to be phased out decades ago. However, Duke University chemist Heather Stapleton found chlorinated tris to be the most common flame retardant in baby products since pentaBDE, a polybrominated diphenyl ether or PBDE, was pulled from the market, according to the Chicago Tribune.[2] Other BFRs, like PBDEs, are still in use today despite growing evidence of their danger to human health. PBDE production constitutes 25 percent of all flame retardant production.[3] A number of flame retardants have been found in sewage sludge (see #Flame Retardants in Toxic Sewage Sludge below for more).

According to chemist Arlene Blum:[4] "When tested in animals, fire retardant chemicals, even at very low doses, can cause endocrine disruption, thyroid disorders, cancer, and developmental, reproductive, and neurological problems such as learning impairment and attention deficit disorder. Ongoing studies are beginning to show a connection between these chemicals and autism in children."

Contents

How Flame Retardants End Up in Human Systems

According to a September 2012 New York Times profile of Blum:

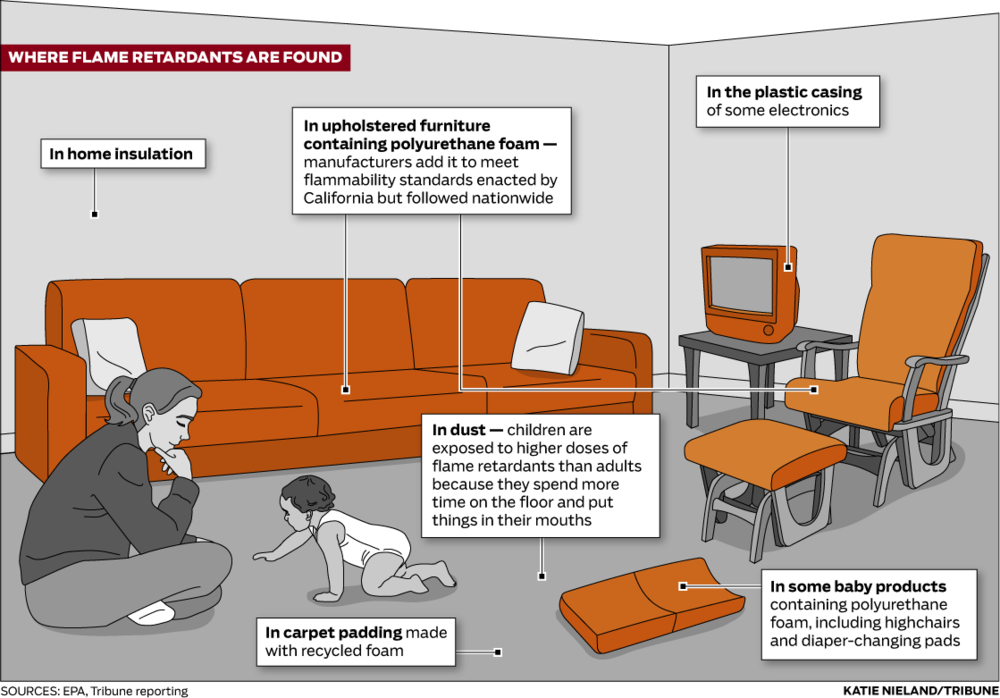

- "Since 1975, an obscure California agency called the Bureau of Home Furnishings and Thermal Insulation has mandated that the foam inside upholstered furniture be able to withstand exposure to a small flame, like a candle or cigarette lighter, for 12 seconds without igniting. Because foam is highly flammable, the bureau’s regulation, Technical Bulletin 117, can be met only by adding large quantities of chemical flame retardants -- usually about 5 to 10 percent of the weight of the foam -- at the point of manufacture. The state’s size makes it impractical for furniture makers to keep separate inventories for different markets, so about 80 percent of the home furniture and most of the upholstered office furniture sold in the United States complies with California’s regulation. 'We live in a foam-filled world, and a lot of the foam is filled with these chemicals,' Blum says.

- "The problem is that flame retardants don’t seem to stay in foam. High concentrations have been found in the bodies of creatures as geographically diverse as salmon, peregrine falcons, cats, whales, polar bears and Tasmanian devils. Most disturbingly, a recent study of toddlers in the United States conducted by researchers at Duke University found flame retardants in the blood of every child they tested. The chemicals are associated with an assortment of health concerns, including antisocial behavior, impaired fertility, decreased birth weight, diabetes, memory loss, undescended testicles, lowered levels of male hormones and hyperthyroidism. . . .

- "Heather Stapleton, a Duke University chemist who conducted many of the best-known studies of flame retardants, notes that foam is full of air. 'So every time somebody sits on it,' she says, 'all the air that's in the foam gets expelled into the environment.' Studies have found that young children, who often play on the floor and put toys in their mouths, can have three times the levels of flame retardants in their blood as their parents. Flame retardants can also pass from mother to child through the placenta and through breast milk."[5]

Where Flame Retardants are Found

Flame Retardants in Tents

Tents, including camping tents, backpacking tents, and children's play tents, are subject to a voluntary industry flammability standard known as CPAI-84. To meet the standard, manufacturers make tents with fabrics treated with flame retardants. A 2014 study found 10 out of 11 tent samples contained flame retardants, including tris(1,3-dichloroisopropyl) phosphate (TDCPP), decabromodiphenyl ether (BDE-209), triphenyl phosphate, and tetrabromobisphenol-A.[6] Additionally, the study found that campers who pitched tents treated with TDCPP had the chemical on their hands afterward.

Flame Retardants in Toxic Sewage Sludge

A 2009 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) study called the Targeted National Sewage Sludge Survey (TNSSS) found that "[a]ll of the flame retardants except one (BDE-138) were essentially found in every sample; BDE-138 was found in 54 out of 84 samples." It had tested for 11 flame retardants, all PBDEs[7] ("28, 47, 66, 85, 99, 100, 138, 153, 154, 183, and 209, which include those identified in the method as being of potential environmental or public health significance"[8]).

That's because, according to In These Times, "[i]n addition to human excreta, sewage sludge is the byproduct of whatever is put down the drain in hospitals, businesses and factories. Consequently it includes toxic heavy metals, flame retardants, pharmaceutical drugs, hormones, endocrine disruptors, carcinogens and steroids (to name a few possible ingredients)."[9]

An April 2012 study by Duke University analyzed "biosolids" samples (a sewage sludge industry Orwellian euphemism for toxic sewage sludge) for "PBDEs, hexabromobenzene (HBB), 1,2-bis(2,4,6-tribromophenoxy)ethane (BTBPE), 2-ethylhexyl 2,3,4,5-tetrabromobenzoate (TBB), di(2-ethylhexyl)-2,3,4,5-tetrabromophthalate (TBPH), the chlorinated flame retardant Dechlorane Plus (syn- and anti-isomers), and the antimicrobial agent 5-chloro-2-(2,4-dichlorophenoxy)phenol (triclosan)." (Triclosan is an antimicrobial compound added to many consumer products.) "PBDEs were detected in every sample analyzed, and ΣPBDE concentrations ranged from 1750 to 6358 ng/g dry weight. Additionally, the PBDE replacement chemicals TBB and TBPH were detected at concentrations ranging from 120 to 3749 ng/g dry weight and from 206 to 1631 ng/g dry weight, respectively. Triclosan concentrations ranged from 490 to 13,866 ng/g dry weight. The detection of these contaminants of emerging concern in biosolids suggests that these chemicals have the potential to migrate out of consumer products and enter the outdoor environment."[10]

A 2008 study by the Swiss College of Agriculture found "two classes of brominated flame retardants: polybrominated diphenyl ethers (BDE28, BDE47, BDE49, BDE66, BDE85, BDE99, BDE100, BDE119, BDE138, BDE153, BDE154, BDE183, BDE209) and hexabromocyclododecane (HBCD) . . . in sewage sludge collected from a monitoring network in Switzerland. . . . DecaBDE, HBCD, penta- and octaBDE showed average specific loads (load per connected inhabitant per year) in sludge of 6.1, 3.3, 2.0 and 0.3mgcap(-1)yr(-1), respectively. . . . Loads from different types of monitoring sites showed that brominated flame retardants ending up in sewage sludge originate mainly from surface runoff, industrial and domestic wastewater."[11]

A 2002 Swedish study published in the same journal analyzed "one hundred and sixteen sewage sludge samples from 22 municipal wastewater treatment plants in Sweden . . . for brominated flame retardants. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) were in the range n.d.–450 ng/g wet weight, tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA) varied between n.d. and 220 ng/g wet weight, 2,4,6-tribromophenol was in the range n.d.–0.9 ng/g wet weight and polybrominated biphenyls were not detected (except for a possible analytical interference). There was a significant variation in the samples among plants. Influence from industries and other local sources can therefore be assumed. The correlation pattern indicated contribution from three different types of technical products; composed of either low-brominated PBDEs, decaBDE or TBBPA."[12]

Results of Long-Term Exposure

According to the Times:

- "The effects of that exposure may be hard to detect in individual children, but scientists can see them when they look across the population. Researchers from the Center for Children’s Environmental Health, at Columbia University, measured a class of flame retardants known as polybrominated diphenyl ethers, or PBDEs, in the umbilical-cord blood of 210 New York women and then followed their children’s neurological development over time. They found that those with the highest levels of prenatal exposure to flame retardants scored an average of five points lower on I.Q. tests than the children with lower exposures, an impact similar to the effect of lead exposure in early life. 'If you're a kid who is at the low end of the I.Q. spectrum, five points can make the difference between being in a special-ed class or being able to graduate from high school,' says Julie Herbstman, the study’s author."[5]

Why the EPA Hasn't Banned Them

The Times noted:

- "Logic would suggest that any new chemical used in consumer products be demonstrably safer than a compound it replaces, particularly one taken off the market for reasons related to human health. But of the 84,000 industrial chemicals registered for use in the United States, only about 200 have been evaluated for human safety by the Environmental Protection Agency [(EPA)]. That’s because industrial chemicals are presumed safe unless proved otherwise, under the 1976 federal Toxic Substances Control Act" (TSCA).[5]

Senators Frank R. Lautenberg (D-NJ) and Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) have pointed out that TSCA (pronounced TOSS-ka) is so flawed that it prevents the EPA "from taking even modest steps to collect adequate data on chemical risks or to appropriately manage those risks."[13] In an effort to address these shortcomings, Sen. Lautenberg (and 24 co-sponsors) introduced the "Safe Chemicals Act" (S. 847), which amends TSCA "to ensure that risks from chemicals are adequately understood and managed."[14] Among other things, it would promote the use of safer alternatives to hazardous chemicals and require chemicals currently on the market to meet a risk-based safety standard.[15]

Chemical Industry "Distorting Science"

According to the Chicago Tribune in an influential investigation of flame retardants and the chemical industry cover-up of their hazards published in May 2012, "the chemical industry has manipulated scientific findings to promote the widespread use of flame retardants and downplay the health risks . . . The industry has twisted research results, ignored findings that run counter to its aims and passed off biased, industry-funded reports as rigorous science. As a result, the chemical industry successfully distorted the basic knowledge about toxic chemicals that are used in consumer products and linked to serious health problems, including cancer, developmental problems, neurological deficits and impaired fertility. Industry has disseminated misleading research findings so frequently that they essentially have been adopted as fact. They have been cited by consultants, think tanks, regulators and Wikipedia, and have shaped the worldwide debate about the safety of flame retardants."[16]

A study performed in in 1987 by a team of scientists led by Vytenis Babrauskas investigated whether or not large amounts of flame retardants slowed down fires. The government-funded study did find that these large quantities of fire retardant chemicals slowed the fire by about 15 minutes in a room filled with furniture and televisions packed with the chemicals, as compared to a room full of furniture and televisions without the chemicals. These findings, however, were "grossly distorted" by the chemical industry, according to Babrauskas. "Manufacturers of flame retardants would repeatedly point to this government study as key proof that these toxic chemicals -- embedded in many common household items -- prevented residential fires and saved lives," according to the Tribune. But Babrauskas said his study "was not based on real-world conditions" because "[t]he small amounts of flame retardants in typical home furnishings . . . offer little to no fire protection. . . . 'The fire just laughs at it,' Babrauskas said. . . . 'Industry has used this study in ways that are improper and untruthful,' he said. . . . The bottom line: Household furniture often contains enough chemicals to pose health threats but not enough to stem fires — 'the worst of both possible worlds,' he said."[16]

For much, much more, see the May 2012 Tribune article here. Also see the September 2012 New York Times profile of chemist Arlene Blum that discusses Babrauskas' frustrations with the misuse of his findings here.

"Decades-Long Campaign of Deception"

According to another article in the Chicago Tribune series on flame retardants, there has been "a decades-long campaign of deception that has loaded the furniture and electronics in American homes with pounds of toxic chemicals linked to cancer, neurological deficits, developmental problems and impaired fertility," and it all started with "Big Tobacco." The tobacco industry "wanted to shift focus away from cigarettes as the cause of fire deaths, and continued as chemical companies worked to preserve a lucrative market for their products, according to a Tribune review of thousands of government, scientific and internal industry documents."[17]

- "These powerful industries distorted science in ways that overstated the benefits of the chemicals, created a phony consumer watchdog group that stoked the public's fear of fire and helped organize and steer an association of top fire officials that spent more than a decade campaigning for their cause.

- "Today, scientists know that some flame retardants escape from household products and settle in dust. That's why toddlers, who play on the floor and put things in their mouths, generally have far higher levels of these chemicals in their bodies than their parents.

- "Blood levels of certain widely used flame retardants doubled in adults every two to five years between 1970 and 2004. More recent studies show levels haven't declined in the U.S. even though some of the chemicals have been pulled from the market. A typical American baby is born with the highest recorded concentrations of flame retardants among infants in the world.

- "People might be willing to accept the health risks if the flame retardants packed into sofas and easy chairs worked as promised. But they don't."[17]

EPA Collusion

According to the Tribune, the EPA "has allowed generation after generation of flame retardants onto the market and into American homes without thoroughly assessing the health risks. The EPA even promoted one chemical mixture as a safe, eco-friendly flame retardant despite grave concerns from its own scientists about potential hazards to humans and wildlife."[17]

According to award-winning environmental journalist Valerie J. Brown, "In a 2005 report on flame-retardant alternatives the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) indicated that the unidentified proprietary components of Firemaster 550 have 'low' or 'moderate' hazard for human health effects and low hazard for persistence and bioaccumulation. However, the supporting documentation behind these determinations reveals a dearth of hard data. For instance, the sections on “proprietary F” and “proprietary H” (each identified only as a “halogenated aryl ester”) contain no data at all regarding chronic or subchronic toxicity, carcinogenicity, neuro-toxicity, immuno-toxicity, genotoxicity, or effects on reproduction or development; the determinations instead were based on expert judgment. The EPA also estimated the degradation products to be high for persistence, as is now being seen."[18] Please see the article for much more information.

A Flame Retardant Front Group the Tobacco Industry Could Love

According to a third Tribune article, several decades ago "[s]moldering cigarettes were sparking fires and killing people. . . . The industry insisted it couldn't make a fire-safe cigarette that would still appeal to smokers and instead promoted flame retardant furniture -- shifting attention to the couches and chairs that were going up in flames. But executives realized they lacked credibility, especially when burn victims and firefighters were pushing for changes to cigarettes. So Big Tobacco launched an aggressive and cunning campaign to 'neutralize' firefighting organizations and persuade these far more trusted groups to adopt tobacco's cause as their own. The industry poured millions of dollars into the effort, doling out grants to fire groups and hiring consultants to court them."[19]

- "The tobacco industry's biggest prize? The National Association of State Fire Marshals, which represented the No. 1 fire officials in each state.

- "A former tobacco executive, Peter Sparber, helped organize the group, then steered its national agenda. He shaped its requests for federal rules requiring flame retardant furniture and fed the marshals tobacco's arguments for why altering furniture was a more effective way to prevent fires than altering cigarettes.

- "For years, the tobacco industry paid Sparber for what the marshals mistakenly thought was volunteer work. . . .

- "This clever manipulation set the stage for a similar campaign of distortion and misdirection by the chemical industry that continues to this day."[19]

Citizens for Fire Safety was founded in 2007[20] by Albemarle Corporation, Chemtura Corporation, and ICL Industrial Products.[21]

Of the flame retardant chemical industry's "misleading campaign to fuel demand," the Tribune reported, "There is no better example of these deceptive tactics than the Citizens for Fire Safety Institute."[17] Here is how it describes the front group:

In the website photo, five grinning children stand in front of a red brick fire station that could be on any corner in America. They hold a hand-drawn banner that says "fire safety" with a heart dotting the letter "i."

Citizens for Fire Safety describes itself as a group of people with altruistic intentions: "a coalition of fire professionals, educators, community activists, burn centers, doctors, fire departments and industry leaders, united to ensure that our country is protected by the highest standards of fire safety."

Heimbach summoned that image when he told lawmakers that the organization was "made up of many people like me who have no particular interest in the chemical companies: numerous fire departments, numerous firefighters and many, many burn docs."

But public records demonstrate that Citizens for Fire Safety actually is a trade association for chemical companies. Its executive director, Grant Gillham, honed his political skills advising tobacco executives. And the group's efforts to influence fire-safety policies are guided by a mission to "promote common business interests of members involved with the chemical manufacturing industry," tax records show.

Its only sources of funding — about $17 million between 2008 and 2010 — are "membership dues and assessments" and the interest that money earns.

The group has only three members: Albemarle, ICL Industrial Products and Chemtura, according to records the organization filed with California lobbying regulators. Those three companies are the largest manufacturers of flame retardants and together control 40 percent of the world market for these chemicals, according to The Freedonia Group, a Cleveland-based research firm. . . .

Citizens for Fire Safety has portrayed its opposition as misguided, wealthy environmentalists. But its opponents include a diverse group of public health advocates as well as firefighters who are alarmed by studies showing some flame retardants can make smoke from fires even more toxic.

Matt Vinci, president of the Professional Fire Fighters of Vermont, faced what he called "dirty tactics" when he successfully lobbied for his state to ban one flame retardant chemical in 2009.

Particularly offensive to Vinci were letters Citizens for Fire Safety sent to Vermont fire chiefs saying the ban would "present an additional hazard for those of us in the fire safety profession." But the letter's author wasn't a firefighter; he was a California public relations consultant. . . .

The group also has misrepresented itself in other ways. On its website, Citizens for Fire Safety said it had joined with the international firefighters' association, the American Burn Association and a key federal agency "to conduct ongoing studies to ensure safe and effective fire prevention."

Both of those organizations and the federal agency, however, said that simply is not true.

"They are lying," said Jeff Zack, a spokesman for the International Association of Fire Fighters. "They aren't working with us on anything."

After inquiries from the Tribune, Citizens for Fire Safety deleted that passage from its website.[17]

Chemtura also still funds the National Association of State Fire Marshals, according to the Tribune.[19]

(The Tribune said it "discovered details about Big Tobacco's secretive campaign buried among the 13 million documents cigarette executives made public after settling lawsuits that recouped the cost of treating sick smokers."[19] To search through documents in the "Tobacco Library" yourself, go here. To more easily find information about tobacco industry behavior, visit SourceWatch's TobaccoWiki here.)

Articles and Resources

Related SourceWatch Articles

- American Chemistry Council

- Citizens for Fire Safety

- Albemarle

- ICL Industrial Products

- PBDEs

- Brominated flame retardants

- Biosolids

- Sewage sludge

- Food Rights Network

External Resources

External Articles

- Chicago Tribune series on flame retardants, "Playing with Fire," May 2012.

- Dashka Slater, "How Dangerous Is Your Couch?," New York Times, September 6, 2012.

- Valerie J. Brown, "Why is it So Difficult to Choose Safer Alternatives for Hazardous Chemicals?," Environmental Health Perspective (Volume 120), July 2, 2012, pp. 280-283.

- Arlene Blum, "Flame retardants, policy, and public health: past and present," 4th International Conference on the History of Occupational and Environmental Health, June 2010.

- Arlene Blum and Linda Birnbaum, "Halogenated Flame Retardants in Consumer Products: Do the Fire Safety Benefits Justify the Health and Environmental Risks?," 5th International Symposium on Brominated Flame Retardants, April 2010.

- Arlene Blum, "Killer Couch Chemicals," Huffington Post, August 16, 2007.

- Arlene Blum, "Chemical Burns," New York Times, November 19, 2006.

- Linda S. Birnbaum and Daniele F. Staskal, "Brominated Flame Retardants: Cause for Concern?", Environmental Health Perspectives, January 1, 2004.

- Heather M. Stapleton, Susan Klosterhaus, Sarah Eagle, Jennifer Fuh, John D. Meeker, Arlene Blum, and Thomas F. Webster, "Detection of Organophosphate Flame Retardants in Furniture Foam and U.S. House Dust," Environmental Science & Technology, August 13, 2009.

References

- ↑ Linda S. Birnbaum and Daniele F. Staskal, "Brominated Flame Retardants: Cause for Concern?", Environmental Health Perspectives, January 1, 2004, Accessed August 10, 2010

- ↑ Michael Hawthorne, Toxic roulette, Chicago Tribune, May 10, 2012

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control, Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals

- ↑ Arlene Blum, "Killer Couch Chemicals," Huffington Post, August 16, 2007, accessed August 9, 2010

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 Dashka Slater, "How Dangerous Is Your Couch?," New York Times, September 6, 2012

- ↑ Alexander S. Keller, Nikhilesh P. Raju, Thomas F. Webster, and Heather M. Stapleton, "Flame Retardant Applications in Camping Tents and Potential Exposure," Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett., 2014, 1 (2), pp 152–155 DOI: 10.1021/ez400185y, January 7, 2014.

- ↑ EPA, Biosolids: Targeted National Sewage Sludge Survey Report - Overview, regulatory agency overview of study report, January 2009

- ↑ EPA, Targeted National Sewage Sludge Survey Sampling and Analysis Technical Report, regulatory agency study report, January 2009

- ↑ Patrick Trahey, Sewage Sludge Everlasting, In These Times, April 19, 2010

- ↑ Elizabeth F. Davisa, Susan L. Klosterhausb, and Heather M. Stapleton, Measurement of flame retardants and triclosan in municipal sewage sludge and biosolids, Environment International (Volume 40), April 2012, pp. 1-7

- ↑ Kupper T, de Alencastro LF, Gatsigazi R, Furrer R, Grandjean D, and Tarradellas J, Concentrations and specific loads of brominated flame retardants in sewage sludge, Chemosphere (Volume 71, Issue 6), April 2008, pp. 1173-80

- ↑ Karin Öberga, Kristofer Warmanb, and Tomas Öberg, Distribution and levels of brominated flame retardants in sewage sludge, Chemosphere (Volume 48, Issue 8), September 2002, pp. 805–809

- ↑ Sens. Frank R. Lautenberg and Sheldon Whitehouse, Letter to Cass Sunstein, then Administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), Office of Management and Budget (OMB), September 9, 2011

- ↑ U.S. Senate, S. 847, proposed legislation, 112th Congress, introduced April 14, 2011, approved by the Committee on Environment and Public Works on July 25, 2012

- ↑ Rebekah Wilce, Death by Delay: Obama Team Stalls on Chemical Regulation, PRWatch.org, March 26, 2012

- ↑ Jump up to: 16.0 16.1 Sam Roe and Patricia Callahan, Distorting science: Makers of flame retardants manipulate research findings to back their products, downplay health risks, Chicago Tribune, May 9, 2012

- ↑ Jump up to: 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Patricia Callahan and Sam Roe, Fear fans flames for chemical makers, Chicago Tribune, May 6, 2012

- ↑ Valerie J. Brown, Why is it So Difficult to Choose Safer Alternatives for Hazardous Chemicals?, Environmental Health Perspectives (Volume 120), July 2, 2012, pp. 280-283

- ↑ Jump up to: 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Patricia Callahan and Sam Roe, Big Tobacco wins fire marshals as allies in flame retardant push, Chicago Tribune, May 8, 2012

- ↑ Citizens for Fire Safety, Citizens for Fire Safety, organizational website, archived by the "WayBack Machine" on June 26, 2011

- ↑ Citizens for Fire Safety, Citizens for Fire Safety, organizational website, accessed September 7, 2012