K12 Inc.

|

Find the privatizers and profiteers at OutsourcingAmericaExposed.org. |

|

Learn more about corporations VOTING to rewrite our laws. |

K12 Inc. is a publicly-traded (NYSE: LRN) for-profit, online education company headquartered in Herndon, Virginia. Part of the business has been rebranded as Fuel Education, formerly known as K12 for Schools and Districts.[1][2] As K12 Inc. notes in its annual report, "most of (its) revenues depend on per pupil funding amounts and payment formulas" from government contracts for virtual public charter schools and "blended schools" (combining online with traditional instruction) among other products. In 2014, K12 Inc. took in $919.6 million from its business.[3]

As online education has come under increasing criticism for poor results, including by charter school proponents such as the Walton Family Foundation, K12 has been shifting its business model away from managing its own schools to selling materials and content to other providers.[4] See below.

K12 Inc. was founded by former Goldman Sachs executive Ron Packard and former United States Secretary of Education and right-wing talk show host William Bennett in 1999.[5][6] Packard was able to start K12 Inc. with $10 million from convicted junk-bond king Michael Milken and $30 million more from other Wall Street investors.[7][8] For more on this, read PRWatch investigation: "From Junk Bonds to Junk Schools: Cyber Schools Fleece Taxpayers for Phantom Students and Failing Grades", October 2013.

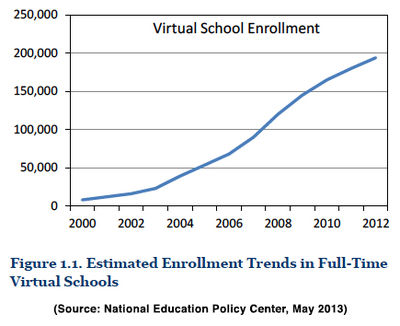

K12 Inc., both on its own and as a member of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), has pushed a national agenda to replace bricks and mortar classrooms with computers and to replace actual teachers with "virtual" teachers. K12 Inc. operated 58 full-time virtual schools and enrolled close to 77,000 students in the 2010-2011 school year, according to a May 2013 report by the National Education Policy Center (NEPC, a research organization at the University of Colorado at Boulder).[9] Many have questioned the company's extraordinary revenue and profit levels, largely generated at taxpayers' expense.[10][11]

Although K12 Inc. was born on Wall Street, some on Wall Street have turned against the model. As of September 2013, hedge fund manager Whitney Tilson announced he was shorting K12 Inc. stock, effectively betting that the company would fail with an unsustainable education model.[12][13] Tilson said in a September 2013 presentation document that although average revenues per student are on the rise and the concept of online education has "strong political support, especially among Republicans" as well as "enormous buzz," "K12's aggressive student recruitment has led to dismal academic results by students and sky-high dropout rates, in some cases more than 50% annually" and "there have been so many regulatory issues and accusations of malfeasance that I'm convinced the problems are endemic."[14]

The efficacy of the model has also been questioned by the company's shareholders in a lawsuit alleging that the firm violated securities law by making false statements to investors about students' performance on standardized tests and boosting its enrollment and revenues through "deceptive recruiting," according to the Washington Post (see below for more).[15]

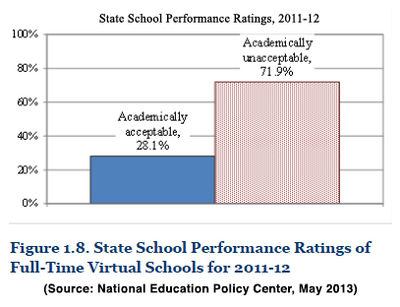

For many years, there was simply no data on virtual school performance. In 2012-13, state data became available indicating poor student achievement, as well as high student turnover, high student-teacher radios, uncertified teachers in some states (such as Florida),[16] and a funding formula that often gives companies extended periods of public funds for a child when the child may only stay at the cyber school for a brief period of time.[9] This new information has led some educators to call for a moratorium on the growth of full-time charter schools until policy-makers can assess the reasons for their significant failure to educate children.[17] Educators also question the appropriateness of taking children as young as five out of a classroom of their peers and putting them in front of a computer screen.[18][19] Low-paid teachers can be assigned as many as 250 students at a time -- as they were at Agora Cyber Charter School in Pennsylvania, according to the New York Times -- and they communicate with their pupils rarely, primarily online and sometimes by phone.[11]

Contents

- 1 Data Shows that Cyber Schools Perform Significantly Worse than Brick-and-Mortar Schools

- 1.1 Walton Family Foundation-Funded Studies Document Terrible Performance of Online "Virtual" Charter Schools (2016)

- 1.2 Tennessee K12 Inc. Online School Performs Worst in State, But Gets "Reprieve"

- 1.3 K12 Inc. School in Colorado Denied Charter School Authorization for Sub-Par Performance, Forced to Pay Back $800,000 to State

- 1.4 Pennsylvania's Agora Cyber Charter School Students Falling Behind

- 1.5 Wisconsin School Districts Drop K12 Inc. for Prioritizing Profits Over Students

- 2 Other Controversies

- 2.1 K12 Settles Lawsuit with California Department of Justice for 168.5 Million Dollars

- 2.2 Drop Out Rate Extremely High, but School Funding Formulas Continue to Pay for Students for Extended Periods

- 2.3 Class Action Lawsuit by Investors Against K12 Inc. for False Statements Re: Student Performance and Deceptive Recruiting Practices

- 2.4 Lawsuit Alleges K12 Misled Investors, CEO Profited

- 2.5 NCAA Says K12 Courses Don't Count for Student-Athletes

- 2.6 Former Staff Allege "Fraudulent Tactics to Mask Astronomical Rates of Student Turnover"

- 2.7 Spending Taxpayer Dollars on Advertising to Pump Up Attendance Numbers and Taxpayer Subsidies

- 2.8 Allegations of Uncertified Teachers in Florida

- 2.9 Questionable Relationship with Non-Profit Charter Holders

- 2.10 Teaching Quality

- 2.11 Failure to Comply with Federal Special Education Standards

- 2.12 Astroturf Support for Virtual Education

- 3 Ties to the American Legislative Exchange Council

- 4 Ties to Jeb Bush's Foundation for Excellence in Education

- 5 Political Activity

- 6 Fine Print Follies

- 7 Chief Executive Officer

- 8 Personnel

- 9 Contact Information

- 10 Resources and Articles

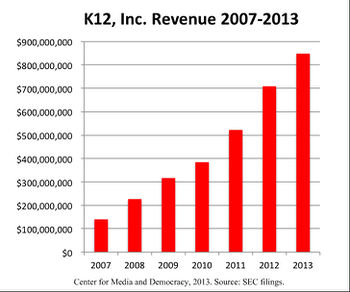

PROFITS AND OWNERSHIP: In recent years, K12 Inc. has experienced a windfall in profit growth, siphoning off taxpayer funds from public education services while state governments and others have struggled economically in the wake of the Wall Street crash of 2008. K12 Inc.'s revenues have increased almost fourfold since then, from over $226 million in 2008 to over $919 million in 2014.[3] K12 Inc. reaches students in all 50 states, including more than 2,000 school districts across the United States, and it operates in 85 countries.

According to NEPC, a 125 percent increase in operating profit and more than 200 percent increase in revenue just from 2008 to 2012 is "linked to the sharp increase in K12 Inc. enrollment, which has more than tripled from some 25,000 students it served in 2007. Enrollment has increased despite the fact that during that same period, some of K12 Inc.'s largest schools in Ohio, Colorado and Pennsylvania posted student 'churn' rates as high as 51%, meaning that fewer than half of students who enrolled completed the full academic year."[9]

In its 2014 Annual Report, the company reported that its revenue grew 8.4 percent in fiscal year 2014, with total revenue soaring to $919.6 million, much of that from state and federal education funds.[3]

BUSINESS MODEL: K12 Inc. describes itself as having three lines of business: managed public schools (full-time "virtual" public charter schools and blended schools which combine online time with classroom time), institutional business (which involves formation and sales of educational curricula), and international and private pay business (including managed private schools and independent course sales overseas).[10]

FOUNDING: The company was co-founded in 1999[6] by its current CEO, Ron Packard, a former Goldman Sachs mergers and acquisitions expert and consultant with McKinsey & Co.,[7] and by former U.S. Education Secretary under President Ronald Reagan and right-wing talk show host William Bennett, who served as the chairman of K12 Inc.'s board of directors until 2005, when he resigned amid controversial remarks he made surrounding black Americans and crime.[20] Packard was able to start K12 Inc. with $40 million in venture capital from such sources as Andrew Tisch of the Loews billionaire family, Larry Ellison of Oracle, and Knowledge Universe, a for-profit education conglomerate chaired by Michael Milken, a felon and former junk bond fraudster.[7] The company was incorporated in Delaware, and went public in 2007.[6]

Data Shows that Cyber Schools Perform Significantly Worse than Brick-and-Mortar Schools

In recent years, there has been an explosion of virtual schools (also called internet schools and cyber schools). From 2008 to 2012, 157 bills passed in 39 states and territories (including the District of Columbia) that expand online schooling, regulate virtual education, or modify existing regulations, according to a National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) database.[21] Many of these bills are attributable to American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) politicians. As discussed below, ALEC passed a "model" virtual schools act in 2004.

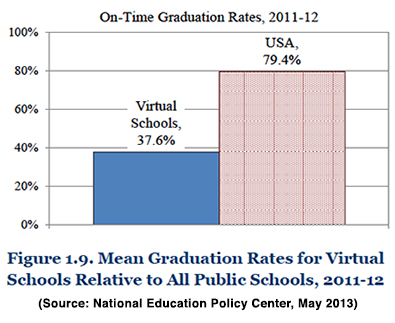

Until recently, data on performance was scarce, but educators at the National Education Policy Center did two of the first empirical studies in 2012 and 2013 on the effectiveness of full-time online schools. The authors concluded that despite the amount of taxpayer dollars going towards these schools, there is "very little solid evidence to justify the rapid expansion of virtual education." One of the studies, looking at state data on performance, shows major problems with cyber schools. The 2013 report by NEPC notes, "on the common metrics of Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP), state performance rankings, and graduation rates, full-time virtual schools lag significantly behind traditional brick-and-mortar schools."[9] In particular, only 27.7 percent of K12 Inc. online schools met AYP in 2010-2011, compared to 52 percent of public schools, and of the 36 K12 Inc. schools that were assigned a school rating by state education authorities, only seven (19.4 percent) of them had ratings that clearly indicated satisfactory status, as of an NEPC report published July 2012 specifically on K12 Inc.'s operations.[17]

The 2013 NEPC study also shows that on-time graduation rates are also much lower at online schools than at all public schools on average in the United States: only 37.6 percent of students at virtual high schools graduate on time, whereas the national average for all public high schools is 79.4 percent, more than twice that.[9] Other critics have wondered where some of the taxpayer dollars directed to online schools end up.

A study of the performance of Pennsylvania online charter schools by the Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) at Stanford University found that 100 percent of cyber charters performed "significantly worse than their traditional public school counterparts in both reading and math.”[22]

A ten-month investigation of Colorado virtual schools found that half of the students of online schools left within a year, and that when they returned to brick-and-mortar schools they were often further behind academically than when they started.[23]

The company has countered critics by citing data from multiple choice tests. According to Politico in 2013, "When the Securities and Exchange Commission questioned K12 about its academic results earlier this year, K12 again pointed to the Scantron data as proof of its success."[24]

Yet those data are “not as accurate as they could be,” K12 Inc. Executive Chairman Nathaniel Davis acknowledged in an interview with Politico.

The Scantron tests are optional, and the company has been comparing a self-selected group of K12 Inc. students to the national norm, which isn’t appropriate, Davis said.[24]

Walton Family Foundation-Funded Studies Document Terrible Performance of Online "Virtual" Charter Schools (2016)

The Walton Family Foundation, a major charter school proponent, concluded that "online education must be reimagined" in an article published in Education Weekly on January 27, 2016.[25] The authors of the piece, Walton Family Foundation directors Marc Sternberg and Marc Holley, explained the results of three independent studies they funded to investigate the performance of virtual charter schools.[25] One such study conducted by Stanford University's Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) revealed that "over the course of a school year, the students in virtual charters learned the equivalent of 180 fewer days in math and 72 fewer days in reading than their peers in traditional charter schools, on average."[25] Sternberg and Holley go on to explain the implications of these findings, saying "if virtual charters were grouped together and ranked as a single school district, it would be the ninth-largest in the country and among the worst-performing."[25] As a result, Sternberg and Holley stated that they will be more cautious with their future online charter school donations and make sure recipients are confronting the problems exposed by the studies.[25]

With Poor Results and Declining Enrollment, K12 Changes Business Model

Two days after the Walton Family Foundation called for a revamping of the online charter education system, K12 held its quarterly shareholder conference call, in which executives discussed an ongoing shift in K12's business model "from running cyber public schools to selling curriculum and other 'platform' services."[26] Between September 2014 and September 2015, enrollment at "managed" virtual schools run by K12 was declining 12 percent, while it was increasing 34.5 percent at "non-managed" schools, which pay for K12's content and platform but which are run by other entities.[4]

On the call, the largest private online charter school corporation in the country still reported $208 million in revenue for the fourth quarter, leading to a 10 percent hike in K12 Inc.'s stock price.[26]

Tennessee K12 Inc. Online School Performs Worst in State, But Gets "Reprieve"

Students at K12 Inc.'s Tennessee Virtual Academy (TVA), which operates as a public school under the auspices of Union County Public Schools, made far less educational progress than any other school in the state in the 2012-2013 school year, according to the Tennessee Department of Education. According to The Tennesseean, TVA students "made less progress as a group in reading, math, science and social studies than students enrolled in all 1,300 other elementary and middle schools who took the same tests. The school fell far short of state expectations for the second year in a row."[27]

Despite these repeatedly poor results, lobbying efforts by K12 Inc. ensured that the school would remain open for the 2013-2014 school year. When Governor Bill Haslam's administration proposed a bill in January 2013 that would let it limit enrollment or shut down a school that underperformed for two years, K12 Inc. "waged a public relations campaign that involved the school's teachers, some of its parents and lobbyists." According to The Tennesseean: "[T]he company's longtime lobbyist, the powerful Nashville firm of McMahan Winstead, worked against the bill," yielding an amendment stretching the time limit to three years, but not satisfied, K12 Inc. "hired the Ingram Group, the firm founded by Haslam's adviser, Tom Ingram." The lobbying did not succeed in further changes to the legislation, however, and Governor Haslam signed the bill in May 2013.[27]

K12 Inc. School in Colorado Denied Charter School Authorization for Sub-Par Performance, Forced to Pay Back $800,000 to State

In November 2012, the Colorado Charter School Institute (CCSI), an independent state agency that authorizes charter schools in the state, denied K12 Inc.'s 5,000-student Colorado Virtual Academy's application for charter school authorization. In its decision, CCSI cited concerns that the school's student performance was below the 10th percentile of schools statewide, that it had a student turnover of 25 percent for elementary and middle school students and 50 percent for high school students, that the school's board had not followed through on a rubric for holding K12 Inc. accountable, and that its curriculum did not adequately "address the increased number of at-risk student populations." The news of the CCSI's denial reportedly impacted K12 Inc.'s publicly trade stock in a negative fashion.[28][9]

An earlier state audit found that K12 Inc.'s Colorado Virtual Academy "counted about 120 students for state reimbursement whose enrollment could not be verified or who did not meet Colorado residency requirements," and auditors "ordered the reimbursement of more than $800,000" to the state, according to the New York Times (see the audit report here).[11][29] A ten-month investigation of Colorado virtual schools in 2011 found that half of the students of online schools in the state left within a year, and that when they returned to brick-and-mortar schools they were often further behind academically than when they started.[30]

Pennsylvania's Agora Cyber Charter School Students Falling Behind

The Pennsylvania General Assembly allowed for the establishment of cyber charter schools in the state with the passage of Act 88 in 2002, according to Evergreen Education Group (a consulting firm that prepares an annual review of policy and practice for online learning).[31][32] The bill was passed at the behest of Republican Governor Mark Schweiker's administration, according to the pro-education privatization Reach Foundation,[33] and he signed it into law June 29, 2002.[34] (An earlier 1997 charter school law, Act 22, had allowed for the creation of some online charter schools, although the law did not anticipate this, according to Ron Cowell of the Education Policy and Leadership Center.[35] That law is very similar to the American Legislative Exchange Council's 1995 "Charter Schools Act.")

According to the New York Times, in Pennsylvania, online schools "bill each of their students' home districts the full per-pupil amount that the district would otherwise have spent to educate that child in a brick-and-mortar school, which averages over $11,000 per student, making Pennsylvania one of the most lucrative states in the nation in which to operate for-profit online schools and harming public schools."[36]

But a study of the performance of Pennsylvania online charter schools by the Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) at Stanford University found that 100 percent of cyber charters performed "significantly worse than their traditional public school counterparts in both reading and math.”[37]

At K12 Inc.'s Agora Cyber Charter School, which produces more than 10 percent of the company's revenue, nearly 60 percent of students are behind grade level in math, nearly 50 percent are behind in reading, and a third do not graduate on time, according to the New York Times.[11]

In addition, withdrawal rates at K12 Inc. schools are persistently very high. For example, in 2009-2010, 2,688 students withdrew from Agora.[11]

Wisconsin School Districts Drop K12 Inc. for Prioritizing Profits Over Students

In August 2012, two Wisconsin school districts with online education programs--Grantsburg's iForward and Waukesha's eAchieve Academy--announced that they would not renew their contracts with K12 Inc. for the 2012-2013 school year, according to the Green Bay Press Gazette.[38]

Rick Nettesheim, principal of eAchieve, told the paper that his school is glad to be free of the company: "It's been our experience that the interest of their shareholders is the most critical deciding factor when decisions are being made. They may say they have the best interests of students in mind, and I'm sure their teachers care about their students just as much as our teachers care about students, but the people making decisions do have to answer to shareholders, and I think that's a conflict of interests."[38]

Other Controversies

K12 Settles Lawsuit with California Department of Justice for 168.5 Million Dollars

K12 Inc. settled a lawsuit with the Bureau of Children’s Justice and False Claims Unit of the California Department of Justice for $168.5 million. The lawsuit filed by the attorney general’s office alleged that K12 and the California Virtual Academies (CAVA) schools it manages were publishing misleading information intended to convince parents to enroll their kids in K12 schools, submitting “inflated student attendance numbers" and influencing “nonprofit online charter schools to enter into unfavorable contracts that put them deep in a financial hole." The attorney general's office also alleged that K12 and the CAVA schools received “more dollars in state funding from the California Department of Education than they were entitled to." According to California Department of Justice K12 is required to “provide approximately $160 million in debt relief to the non-profit schools it manages” and pay $8.5 million in settlement claims. They are also required to reform their contacts with the 14 CAVA schools, be subjected to an independent review over their services for students with disabilities, “ensure [the] accuracy of all advertisements, provide teachers with sufficient information and training to prevent improper claiming of attendance dollars, and change policies and practices to prevent the kinds of conduct that led to this investigation and agreement."[39]

Drop Out Rate Extremely High, but School Funding Formulas Continue to Pay for Students for Extended Periods

K12 Inc. CEO, Ronald Packard repeatedly describes growing student enrollments as the company's "manifest destiny."[40] This manifest destiny is producing an extremely high drop out rate also called a "churn rate." Anecdotal reports and studies put the churn rate at some K12 schools as high as 57%.

Luis Huerta, a Columbia University education specialist, calculated a churn rate for K12's Agora Cyber Charter School at 57 percent.[41] At Ohio Virtual Academy, another K12 Inc. school, the "churn rate" in 2009-10 was almost 50 percent, according to NewsWorks.[42]

A state audit of K12 Inc.'s Colorado Virtual Academy found that the state paid for students who were not attending the school and K12 Inc. was ordered to return $800,000.[11] (See the audit report here).[43]

Despite much lower operating costs, “the online companies collect nearly as much taxpayer money in some states as brick-and-mortar charter schools. In Pennsylvania, about 30,000 students are enrolled in online schools at an average cost of about $10,000 per student. The state auditor general, Jack Wagner, said that is double or more what it costs the companies to educate those children online,” reports the New York Times.[11] “It’s extremely unfair for the taxpayer to be paying for additional expenses, such as advertising,” Mr. Wagner told the Times, and some of the money is also spent on lobbying.

In 2012, after student proficiency dropped at nine out of the 10 cyber charters in Pennsylvania, Wagner announced that taxpayers overpay the state’s cyber charters by about $100 million a year and recommended changes to the school funding formula to protect taxpayers, reports Politico.[24]

The funding formula in many states works like this, explains education experts: "The kids enroll, you get the money, the kids disappear, Gary Miron of Western Michigan University told the New York Times.

Class Action Lawsuit by Investors Against K12 Inc. for False Statements Re: Student Performance and Deceptive Recruiting Practices

The problems with the K12 Inc. model were highlighted by the details revealed in a shareholder lawsuit. In January 2012, a K12 Inc. shareholder sued K12 Inc. for securities fraud in federal court, alleging that the firm made false statements to investors about students' performance on standardized tests and boosted its enrollment and revenues through "deceptive recruiting."[15] In June 2012, the class of shareholders filed an amended complaint, which includes information from interviews with former K12 teachers and staff, which can be accessed here.

The class action lawsuit was filed after a series of news reports (in particular a New York Times article of December 12, 2011[11] and an Associated Press article of December 16, 2011) found a mismatch between K12 Inc. student achievement and statements made by CEO Ron Packard. After the articles were published, K12 Inc. stock dropped 34 percent.[15] The plaintiffs "alleged that the company misled shareholders by overstating its academic performance, and by not providing accurate information about student-to-teacher ratios and how students are recruited," according to Education Week.[44]

Shareholders claimed that "the company did not disclose the churn rates during conference calls" with stockholders or in the documents it filed. As a result, the plaintiffs contended, the price at which K12 Inc.'s stock was traded was artificially inflated.[42]

K12 Inc. reached a tentative settlement agreement in March 2013, in which it agreed to pay $6.75 million to plaintiffs who brought the suit, while company officials continue to deny any claims of wrongdoing.[44]

Lawsuit Alleges K12 Misled Investors, CEO Profited

Another lawsuit filed in April 2014 claimed that K12 "misled investors by making wildly positive statements about the company and its future, only to reveal it was actually financially off-target," and that CEO Ron Packard reaped $6.4 million by selling off his own stock before the negative announcement.[45]

NCAA Says K12 Courses Don't Count for Student-Athletes

In April 2014, the NCAA issued a document announcing that coursework completed at 24 K12-affiliated schools would not count for student-athletes' eligibility. K12's schools had been placed under "extended evaluation" in 2012. The NCAA did not provide an explanation of their decision when contacted by media.[46]

Former Staff Allege "Fraudulent Tactics to Mask Astronomical Rates of Student Turnover"

Much was learned about the business practices of K12 Inc. from the 2012 class-action investor lawsuit described above. Dozens of former employees claimed that the company "used dubious and sometimes fraudulent tactics to mask astronomical rates of student turnover in its national network of cyber charter schools," according to the Huffington Post.[36]

At the beginning of the 2010-11 school year, K12 Inc.'s Agora Cyber Charter School enrolled 5,353 students. By the end of that year, the school's enrollment had increased to 6,475. But almost 2,400 students withdrew from Agora during the school year.[36] At Ohio Virtual Academy, another K12 Inc. school, the "churn rate" in 2009-10 was almost 50 percent, according to NewsWorks.[42]

According to these former employees, the churn rate at the company's cyber schools was part of a "self-perpetuating cycle. To increase revenues, the suit alleges, the company aggressively recruited as many students as possible," including some who were not properly prepared for K12 Inc.'s full-time online schooling. When students struggled, they claim, "company officials told teachers to keep the students on the schools' rolls by manipulating attendance data and inflating students' grades," according to NewsWorks.[42]

These claims were listed by anonymous "confidential witnesses" in court documents. Many of the allegations come from people who worked for Pennsylvania's Agora Cyber Charter School, which enrolls roughly a quarter of the 32,000 Pennsylvania students that have opted for online schools.[36]

In one example, a former Agora teacher said that the school continued to bill the home school district of one special education student who was absent for 140 consecutive days, even though Pennsylvania requires that cyber charter students who miss 10 straight days be reported as withdrawn. The teacher stated, "What Agora does is keep the kid in inactive limbo and keep billing."[36]

Former employees also described the company's "high-pressure" approach to student recruitment, involving "call centers" with "enrollment consultants" who received "commissions and perks" for hitting "enrollment quotas" -- of parents who enrolled their children in the schools. They also alleged that K12 Inc.'s recruitment aggressively "targeted inner-city and at-risk populations," even though a senior company official admitted that "the K12 curriculum wasn't built for 'inner-city kids.'" Why? According to the lawsuit, K12 Inc.'s motive was "higher potential profit." The "hard-to-serve students were more likely [to] be chronically truant and would thus use fewer of the company's resources," according to NewsWorks.[42]

In their lawsuit, K12 Inc. investors claimed that "the company did not disclose the churn rates during conference calls" with stockholders or in the documents it filed. As a result, the plaintiffs contended, the price at which K12 Inc.'s stock was traded was artificially inflated.[42]

Spending Taxpayer Dollars on Advertising to Pump Up Attendance Numbers and Taxpayer Subsidies

A 2012 article in USA Today revealed that "virtual, for-profit K-12 schools have spent millions in taxpayer dollars on advertising" -- $94.4 million from 2007 to 2012. K12 Inc. itself, the paper found, "spent about $21.5 million in just the first eight months of 2012." A company spokesperson "declined to say what percentage of K12's per-pupil expenses goes to advertising," but a University of Colorado professor estimated that K12 Inc. was on pace by November "to spend about $340 per student on advertising, or about 5.2 percent of its per-pupil public expenditures" in 2012.[47]

USA Today also noted where the advertising dollars were focused: in 2012, K12 Inc. "spent an estimated $631,600 to advertise on Nickelodeon, $601,600 on The Cartoon Network and $671,400 on MeetMe.com, a social networking site popular with teens. It also dropped $3,000 on VampireFreaks.com, which calls itself 'the Web's largest community for dark alternative culture.'"[47]

Jim Buckheit, executive director of the Pennsylvania Association of School Administrators, told the New York Times, "Some of the cyber charter schools have fairly aggressive recruitment campaigns. . . . They have vans, billboards, TV and radio ads. They set up recruitment meetings in area hotels and invite parents to come."[11]

The massive advertising pulls in parents, students and state money, but students often do not stay in the cyber school, and one study indicates that churn of students could be more than 50 percent in some schools.[9]

Allegations of Uncertified Teachers in Florida

In January 2012, Florida's Department of Education launched an investigation of K12 Inc. over allegations that the company was using uncertified teachers and had asked employees to cover up the practice, according to NPR.[16]

In 2009, K12 Inc. asked Seminole County Public Schools if it could employ uncertified teachers -- each overseen by a "teacher of record," a certified teacher -- to teach some of its online classes. The district denied the request, after consulting with the Florida Department of Education and citing state laws.[16]

But a former K12 Inc. employee forwarded a series of emails to school district officials showing that the company was attempting to claim that certified teachers had taught students they might not even have encountered, even after education officials warned the company that this was not permissible.[16]

According to the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting:[48]

- "In a Feb. 15, 2011 email, K12 Inc.'s Samantha Gilormini, who was in charge of the company's Florida schools, asked teachers to sign class rosters that included students they had not taught. The reason: K12 Inc. needed to use their certification to comply with Florida law on classes for which they didn't have teachers with the required subject certifications. . . .

- "One teacher, Amy Capelle, was given a roster of 112 students. She'd only taught seven of those students, and refused to sign. After learning of this, Seminole County school officials called for a state investigation in 2012."[48]

The Florida Department of Education released its preliminary report in April 2013, in which the inspector general found that K12 Inc. had "assigned teachers working with one district to classes outside their certified fields, and provided records of educators teaching students with whom they had no interaction," according to Education Week.[49]

Seminole County officials had also accused K12 Inc. of using teachers who were not certified in the state of Florida, but the Office of Inspector General said it did not find evidence to back up that allegation.[49]

Questionable Relationship with Non-Profit Charter Holders

Another issue raising red flag is K12 Inc.’s relationship with non-profit charter holders. Most states will only grant charters to non-profit 501 c 3 tax exempt entities, which K12 Inc. is not, so the firm generally signs a long-term contract with a non-profit to run the school. News reports indicate that the relationship is often problematic under state law. A recent example comes from New Jersey. From the Newark Star-Ledger:

- "A contract obtained by The Star-Ledger shows the publicly traded company — which operates charter schools for thousands of students in 27 states and made $30 million in the last school year — selected Newark Prep’s principal, drafted its budget and leased it furniture and equipment.

- "In return, Newark Prep paid the company nearly half a million dollars, or 17 percent of the $2.8 million it received last school year to educate students, according to financial data provided by the school’s board of trustees. This year, as the student body grows, the fees could take up to 40 percent of the school’s revenue, according to the contract.

- "New Jersey law allows for-profit companies to play a big role in public schools.

- "One thing they can’t do is run the place."[50]

Wall Street investor Whitney Tilson, who is betting K12 Inc. will fail, puts it bluntly: “Many of these non-profits are a sham. For all intents and purposes K12 controls and operates and profits from non-profit charter schools in blatant violation of most state law and IRS regulation.”[51]

Teaching Quality

The quality of teaching is also an important issue. In addition to allegations of uncertified teachers in some states and very high student-teacher ratios, online students generally have little interaction with their teachers, as Politico reports:

- "Students can email or call teachers for help or log in to online lectures, but there’s little personal interaction. Many assignments meant to check for understanding are multiple choice; there’s no way to stop kids from looking up the answers online. And the cyber schools, which get additional funds for each student enrolled, have incentives to keep families happy, which some teachers say leads to pressure to award passing grades regardless of effort.

- "'K12 Inc., the largest cyber school management company, explicitly encourages teachers to forgive strings of zeros on homework and quizzes if the student can later show he’s learned the concepts. Otherwise, kids who fail to do any work for weeks might get discouraged and drop out,' said Allison Cleveland, an executive vice president at K12. 'We shouldn’t create an environment for students that they can’t overcome,' she said."[24]

In many instances, motivated parents are clearly the primary teacher, raising the question if taxpayers are subsidizing home-schooling.

Failure to Comply with Federal Special Education Standards

In November 2012, the Georgia Department of Education issued a report finding that K12 Inc.'s Georgia Cyber Academy "has repeatedly failed to comply with the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act and has violated student civil rights by failing to provide services required by the law."[52]

Georgia Cyber Academy has 1,100 special needs students. The Department of Education threatened to close the online school if issues relating to special education were not addressed.[52]

Astroturf Support for Virtual Education

While there are some children and parents committed to the online model for a variety of reasons, in some areas the support for the model appears manufactured.

The New York Times reports that "parent" groups are popping up around the country funded and backed by online firms, and rallies and protests are being sponsored that seem far from genuine.

In Ohio, former State Representative Stephen Dyer "became suspicious when members of the benignly named organization My School, My Choice paraded through his northeastern Ohio district carrying signs attacking him: “Why Won’t Rep. Stephen Dyer let parents choose the best education for their kids?” The group describes itself as a coalition of parents, teachers, and employees of the schools. But Mr. Dyer said that his wife questioned the people carrying the signs and found out they were paid temp agency workers."

Further digging by the Times revealed that the group's incorporation documents named one of the group’s founders as Tim Dirrim, "a Huntington National Bank employee who serves as board president of the Ohio Virtual Academy, which is managed by K-12 and receives more than $60 million a year from the state."[11]

Ties to the American Legislative Exchange Council

K12 Inc. co-founder William Bennett has ALEC ties going back at least to 1985, when he was listed as ALEC's "key issue contact" in the Department of Education.[53] Since then Bennett has been a guest and speaker at ALEC conferences and has worked with ALEC on reports, including on education.[54][55] Bennett was awarded ALEC's Thomas Jefferson Freedom Award in 1994.[56]

K12 Inc.'s former Administrator and Director of School Development, Lisa Gillis, is the most recent known Private Sector Chair of ALEC's Education Task Force Special Needs Subcommittee.[57][58] Three K12 Inc. lobbyists have also been members of ALEC's Education Task Force: Bob Fairbank, Bryan Flood, and Don P. Lee.[59][60]

K12 Inc. was an exhibitor at ALEC's annual meeting in 2011[61] a sponsor of ALEC's 2013 annual meeting,[62] and a "Director's"-level sponsor of ALEC's 2016 Annual Conference.[63]

| About ALEC |

|---|

ALEC is a corporate bill mill. It is not just a lobby or a front group; it is much more powerful than that. Through ALEC, corporations hand state legislators their wishlists to benefit their bottom line. Corporations fund almost all of ALEC's operations. They pay for a seat on ALEC task forces where corporate lobbyists and special interest reps vote with elected officials to approve “model” bills. Learn more at the Center for Media and Democracy's ALECexposed.org, and check out breaking news on our PRWatch.org site.

|

ALEC bills benefiting K12 Inc. are moving across the country. At least 139 bills promoting a private, for-profit education model were introduced in 43 states and the District of Columbia in the first half of 2013, and 31 became law, according to "ALEC at 40: Turning Back the Clock on Prosperity and Progress," an August 2013 report by the Center for Media and Democracy (CMD).[64]

As a 2013 report by the National Education Policy Center notes, "ALEC's model legislation invariably promotes privatization. For example, soon after passage of Tennessee's law making private virtual school operators eligible to receive public funds, K12 Inc. received a contract allowing it to provide virtual education to any Tennessee student in grades K-12."[9]

Virtual Public Schools Act

K12 Inc., together with another for-profit provider of online education, Connections Academy, was heavily involved in ALEC's model bill, the Virtual Public Schools Act, which makes online schools recognized public schools, meaning they must be given the same resources and funding as other public schools in that state. As noted by PRWatch, the ALEC bill "provides that virtual schools should be paid the same per pupil rate as public schools that actually provide bricks and mortar public schools, with desks, heating and A/C, lunch ladies, playgrounds, gyms, in-person teachers, and extracurricular activities like sports, orchestra, and student councils."[5]

In 2004 when the "model" bill was drafted and approved, both K12 Inc. and Connections Academy were part of the "School Choice Subcommittee" of ALEC's Education Task Force, according to an archived version of ALEC's website from February 2005. The subcommittee recommended six bills for adoption, including the "Virtual Public Schools Act." According to ALEC, the bill was drafted by Bryan Flood of K12 along with Mickey Revenaugh of Connections Academy, then-Colorado Representative Don Lee (now a lobbyist for K12, see above), "and the rest of the Subcommittee."[65]

The bill was approved at a closed-door meeting of the ALEC Education Task Force in December 2004, and became model legislation in January 2005, when ratified by ALEC's Board of Directors.[66]

The "Virtual Public Schools Act" is still moving in 2013. Between January and August 2013, state bills similar to ALEC's "model" were introduced in Arizona and Maine and passed in Michigan (HB 4228), according to CMD's report on ALEC bills in 2013.[64]

Previous to 2013, the bill was introduced in at least Mississippi, Maine, Tennessee, Massachusetts, Virginia, and Texas, according to a September 2012 report by In the Public Interest (ITPI). The bill paved "the way for corporations to offer virtual online classes to public school students. In many of these states, legislators that sponsored this legislation were members of ALEC," according to ITPI, which describes itself as "a comprehensive resource center on privatization and responsible contracting."[67]

The legislation offers enormous opportunities for the corporations who helped write it with the help of ALEC. In the states that have passed the model bill, these companies have strong operations. K12 Inc. runs virtual public schools in Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia.[67] As of 2012, K12 Inc. has also been running ads heavily in Wisconsin, since changes signed into law by controversial governor Scott Walker.

After the law was implemented in Tennessee in 2011, as noted by Bill Moyers in his documentary "The United States of ALEC,"[68] K12 Inc. won a no-bid contract from the Union County School District, which became the home of the new Tennessee Virtual Academy.[67] The act states that "students in grades kindergarten through twelve (K-12) who were enrolled in and attended a public school during the previous school year shall be eligible to participate in a virtual public education program." Now Tennessee parents can pull their children out of their local school system and enroll them in Union through the academy. As of 2011, there were about 2,000 students in the virtual school, which is just about the same number of people who reside in Maynardville, the Union County seat. The district gets a small cut of the $5,387 in state aid that attaches to each student, while K12 Inc. gets the rest, according to the New York Times.[69] But the virtual school has performed worse than any other school in the state. For more, see "Tennessee K12 Online School Performs Worst in State, But Gets 'Reprieve'" above.

Ties to Jeb Bush's Foundation for Excellence in Education

K12 Inc. has been a funder of the Foundation for Excellence in Education (FEE), a non-profit education reform advocacy group founded by former Florida governor Jeb Bush, according to emails released by the non-profit privatization resource organization In the Public Interest.[70] FEE is "backed by many of the same for-profit school corporations that have funded ALEC and vote as equals with its legislators on templates to change laws governing America's public schools," as noted by PRWatch. Bush's group is also "bankrolled by many of the same hard-right foundations bent on privatizing public schools that have funded ALEC" and "they have pushed many of the same changes to the law, which benefit their corporate benefactors and satisfy the free market fundamentalism of the billionaires whose tax-deductible charities underwrite the agenda of these two groups."[71]

As In the Public Interest reports, e-mails between FEE and conservative state education officials in Florida, New Mexico, Maine, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, and Louisiana show that the foundation is writing state education laws and regulations in ways that could benefit its corporate funders:

- "The emails, obtained through public records requests, reveal that the organization, sometimes working through its Chiefs For Change affiliate, wrote and edited laws, regulations and executive orders, often in ways that improved profit opportunities for the organization’s financial backers. Bush has been referred to as the “godfather” of Chiefs for Change, an alliance of conservative state superintendents and education department directors with significant authority over purchasing and policy in their states."[72]

Political Activity

K12 Inc. reported $100,000 in lobbying for education causes in 2014 with the firm Akin, Gump, Strauss, Hauer & Feld.[73]

K12 Inc. and its employees "donated $625,000 to politicians of both parties, ballot initiatives and political associations such as the Republican Governors Association" in 2012, according to Politico.[24]

Since 2004, K12 Inc. and its employees have pumped almost $1.3 million into state-level politics in 23 states (as of 2012), including contributions to candidates for office, party committees, and ballot initiatives.[74] In 2012, K12 Inc. gave $300,000 to a group called "Families for Better Public Schools" to support a Georgia ballot initiative to amend the State Constitution so that an appointed statewide commission could authorize new schools.[75][76][52] The ballot measure passed, with proponents like K-12 Inc., Americans for Prosperity, StudentsFirst, and the Walton Family Foundation outspending opponents roughly ten-to-one.[75][52] The amendment was similar to ALEC's Next Generation Charter Schools Act, which includes the idea of an authorizing board to make it easier to establish charter schools over the objections of school districts and other school officials.[75]

K12 Inc. has hired 153 lobbyists in 28 states from 2003 through 2012, according to the National Institute on Money in State Politics.[77]

In Pennsylvania, where ten percent of its revenue is generated, K12 Inc. has spent $681,000 on lobbying since 2007, according to the New York Times.[11] It registered 11 lobbyists in the state from 2007 through 2012, according to the National Institute on Money in State Politics.[78] K12 Inc. has also used ostensibly benign front groups to lobby and organize protests on its behalf. The K12 Inc. funded group Pennsylvania Families for Public Cyber Schools spent $250,000 on lobbying in the last five years, according to the Times. The paper also reports that K12 Inc. is connected to My School, My Choice, a group that organized protests in Ohio against reforming the state formula for financing charter and online schools. The protesters turned out to be paid temp agency workers. Tim Dirrim, the founder of the organization, is the board president of the K12 Inc. managed Ohio Virtual Academy.[11]

Fine Print Follies

"Risk Factors" in SEC Filings

In its SEC filings, K12 Inc. cites several aspects related to government funding and regulation of public education as "risk factors" that may affect its business and future prospects. These risk factors often show the incentives the company has to influence public policy and the direction their advocacy would take.

K12 Inc.'s revenues depend on per pupil funding amounts and payment formulas remaining near the levels existing at the time it executes service agreements with its Managed Public Schools. The company states, "If those funding levels or formulas are materially reduced or modified due to economic conditions or political opposition, new restrictions adopted or payments delayed, our business, financial condition, results of operations and cash flows could be adversely affected."[10]

In addition to funding levels, K12 Inc. also cites opposition to virtual public schools as a threat to revenues, as well as increased lobbying costs.

- "Opponents of virtual and blended public schools have sought to challenge the establishment and expansion of such schools through the judicial process. If these interests prevail, it could damage our ability to sustain or grow our current business or expand in certain jurisdictions.

- "We have incurred significant lobbying costs in several states advocating against harmful legislation which, in our opinion, was aggravated by negative media coverage about us or other Managed School operators."[10]

Chief Executive Officer

Nathaniel A. Davis became CEO and chairman of K12 Inc. in January 2014. He had been a member of the board of directors since 2009. Davis had previously served as managing director of RANND Advisory Group and CEO and president of XM Satellite Radio, and has held executive positions at XO Communications Inc., Nextel Communications, MCI Telecommunications, and MCI Metro. Davis also serves on the boards of Unisys and RLJ Lodging Trust.[79]

His total compensation in 2013, before becoming CEO of K12, was $9,543,607.[80]

Former CEO Ron Packard

- "It’s about educational liberty." - Ron Packard, K12 Inc. CEO[81]

K12 Inc.'s founder and first CEO was former Goldman Sachs executive Ron Packard, who founded the company in 2000. He was previously CEO of Knowledge Schools, part of Michael Milken's Knowledge Universe and Knowledge Learning group.[82] In 2013, Packard received over $4.1 million in total compensation. This compensation included a base salary of $670,836, a "performance" $584,375 bonus, 58,302 shares of restricted stock valued at $1.25 million (fair market value), $1.5 million in stock option awards, and $7,182 in other compensation. He received over $6 million in 2011.[83]

K12 Inc.'s net income (profit after taxes and expenses) was more than $28 million in 2013,[10] but that was the amount left over after it paid its CEO, Ron Packard, over $4.1 million. Its next five highest paid employees received annual compensation of between $758,333 and $3.2 million.[83] K12 Inc. also paid its part-time board members fees of between $71,000 and $167,000, plus stock awards.[84]

From 2009 to 2013, Packard received compensation of over $19.48 million from the company.[85] In 2013, he owned over 2 percent of K12,[86] which had a market cap of around $1.25 billion in September 2013.[87]

Ronald J. Packard was K12's CEO or executive chairman from 2000[88] to 2014, when he resigned in order to lead a new company formed by K12 and Safanad Limited, a global investment firm. Called Pansophic Learning,[89] the new company "would focus on the expansion and integration of technology-based learning programs in pre-K through college across the globe."[90] The Washington Post reported that the new venture would have a global focus, and that "[s]everal businesses within K12 whose combined revenue in 2013 totaled $20.3 million — including the International School of Berne and Capital Education — [would] move to the new company in exchange for minority ownership."[91]

Packard co-founded K12 with former Reagan education secretary William J. Bennett in 2000 after they secured an initial $10 million investment from his boss at Knowledge Learning and convicted junk bond king Michael Milken. The duo also received financial support from Larry Ellison of Oracle.[92]

He also closed a $20 million venture capital funding drive for K12 in 2003 with Constellation Ventures,[93] an affiliate of Bear Stearns Asset Management, [94] one of the Bear Stearns internal hedge funds that blew up in 2007[95] and contributed to the need for a government-backed bailout of the investment bank by JP Morgan.[96] Packard has also teamed up with investment banker Michael Moe, who helped take K12 public.[97] According to The Nation, "Moe has worked for almost fifteen years at converting the K-12 education system into a cash cow for Wall Street."[98]

Packard, born in 1963, grew up in Thousand Oaks, California, the son of a radar and weapon systems engineer for Hughes Aircraft, where he worked as a summer engineer.[99] He then worked in the mergers and acquisitions operation of Goldman Sachs from 1986 to 1988, and at McKinsey and Company from 1989 to 1993.[100] After leaving McKinsey, Packard went to Chile to work on getting government permits for some investors who had "bought title to a large forest."[99] He was then picked up by Milken’s education investment holding firm, Knowledge Universe Learning Group, which appointed him partner, vice president and chief executive (1997-2000);[101] and then by Knowledge Schools, a chain of preschools.[102] Packard also served as a director at LearnNow Inc. (which was bought out by Edison in 2001), and Academy 123 Inc. (2004-2006; now owned by Discovery Communications).[103]

Packard was a defendant in a 2012-2013 securities class action suit over his alleged misstatements to investors on student achievement at K12 schools.[104] The suit claimed that Packard and the company boosted K12's enrollment and revenues through "fraudulent devices, schemes, artifices and deceptive acts, practices, and course of business includ[ing] the knowing and/or reckless suppression and concealment of information regarding K12's excessive churn rates, the poor academic performance of its schools compared with brick and mortar schools, improper practices at several of its schools nation-wide, and enrollment inflation."[105] In March 2013, the parties agreed to settle the suit in return for a payment of $6.75 million by K12's insurance carriers, and the lead plaintiff agreed to withdraw his accusations.[106] The settlement was approved by the court on July 25, 2013.[107]

Packard has agitated for the adoption of online schools for over a decade, including by addressing a "standing room only crowd" of the American Legislative Exchange Council's Education Task Force in December 2002.[108] Packard was flanked at the talk by Jeanne Allen from the Center for Education Reform, who has continued to defend K12 from evidence that it lags behind traditional public schools.[109]

Packard is also a member of Digital Learning Council,[110] a project of Jeb Bush's Foundation for Excellence in Education, which is funded by leading pro-school privatization interests such as the Broad, Gates and Walton Foundations.[111] Bush has said that promoting digital learning, Packard's bread and butter, is at the top of his education reform list because of its capacity "to disrupt the public education system."[112]

According to The Wall Street Journal, "a large part of Mr. Packard's job is dealing with political issues."[113] "We understand the politics of education pretty well," Packard has told investors.[114] He has called lobbying a "core competency" at K12 Inc.,[115] and was himself listed as a registered lobbyist to the New York City government from 2007 to 2010.[116] The New York Times has called for-profit education companies "a lobbying juggernaut in state capitals."[115]

Packard has also dabbled in electoral politics, serving in 2004 on the finance committee for Illinois Senate candidate Jack Ryan (along with William Bennett and then-Goldman Sachs CEO Henry Paulson),[117] a former Goldman Sachs banker who ran against Barack Obama before withdrawing his candidacy after damaging allegations surfaced.[118] Packard and K12's public affairs director Bryan W. Flood also donated to the 2006 campaign of Wisconsin state assembly education chair Rep. Brett Davis (R), who authored a bill benefitting Wisconsin virtual schools, including K12.[119]

Personnel

Board of Directors

As of August 2015:[120]

- Nathaniel A. Davis, Executive Chairman and CEO

- Craig R. Barrett - retired chairman and CEO, Intel Corporation

- Guillermo Bron - managing director of Acon Funds Management LLC, managing member of PAFGP LLC, general partner of Pan American Financial, L.P.

- Fredda Cassell - former partner, PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP; board of directors, United Hospital Fund

- Adam L. Cohn - partner at Knowledge Universe, director at Knowledge Schools LLC, Knowledge Universe Global Inc., Busy Bees Holdings Limited, and Milagro Oil and Gas, Inc

- John M. Engler - former governor of Michigan, president of the Business Roundtable

- Steven B. Fink - director of Nobel Learning Communities, Inc., chairman of Heron International, director of the Foundation of the University of California, Los Angeles

- Mary H. Futrell - former Dean of the Graduate School of Education and Human Development at George Washington University, director at Horace Mann Educators Corporation

- John Q. Reynolds - general partner at Technology Crossover Ventures, on the Board of Directors of Embanet, Global 360, OSIsoft, Seismic Micro-Technology, Solarc, and Webroot

- Andrew H. Tisch - co-chairman of Loews Corporation, vice chairman of Cornell University, trustee at the Brookings Institution, director of CNA Financial Corporation, director of Texas Gas Transmission, LLC and Boardwalk Pipelines, LLC

Former directors include:[121]

- Jane M. Swift

- Thomas Wilford

Executive Management

As of August 2015:[122]

- Nathaniel A. Davis, Chairman and CEO

- Timothy L. Murray, President and COO

- James Rhyu, Executive Vice President and CFO

- Howard D. Polsky, Executive Vice President, General Counsel and Secretary

- Allison Cleveland, Executive Vice President of School Management and Services

- Chuck Sullivan, Executive Vice President and Chief Marketing & Enrollment Officer

- David Cumberbatch, Executive Vice President and Chief Strategy Officer

- Lynda Cloud, Executive Vice President, Products

- Joe Zarella, Executive Vice President of Business Operations

- Bala Balachander, Senior Vice President, Software Product Development and Chief Technology Officer

- Rob Banwarth, Senior Vice President and Chief Information Officer

- Bryan W. Flood, Senior Vice President, Public Affairs

- Margie Jorgensen, Senior Vice President and Chief Academic Officer

- Valerie Maddy, Senior Vice President, Human Resources

- Peter Stewart, Senior Vice President of School Development

Former Executive Management

- Ron Packard, Founder and CEO

- Bruce Davis, Executive Vice President of Worldwide Business Development

- James Donley, Senior Vice President and Chief Information Officer

K12 Inc.'s "Academic Committee"

As of August 2015: [123]

- Craig R. Barrett (Chairperson)

- Nathaniel A. Davis

- Mary H. Futrell

K12 Inc.'s "Audit Committee"

As of August 2015: [123]

- Steven B. Fink (Chairperson)

- Guillermo Bron

- Fredda Cassell

K12 Inc.'s "Compensation Committee"

As of August 2015: [123]

- Andrew H. Tisch (Chairperson)

- Mary H. Futrell

- John Q. Reynolds

K12 Inc.'s "Nominating and Corporate Governance Committee"

As of August 2015: [123]

- Guillermo Bron (Chairperson)

- Adam L. Cohn

- John M. Engler

- Steven B. Fink

- John Q. Reynolds

- Andrew H. Tisch

Contact Information

K12 Inc.

2300 Corporate Park Drive

Herndon, VA 20171

Phone: 866.283.0300

Web: http://www.k12.com

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/K12inc

Twitter: @K12Learn

Resources and Articles

Key Reports

- Stephanie Simon, Cyber schools flunk, but tax money keeps flowing, Politico, September 25, 2013.

- Alex Molnar, Ed., National Education Policy Center, Virtual Schools in the U.S. 2013: Politics, Performance, Policy, and Research Evidence, organizational report, May 2013.

- Gary Miron and Jessica L. Urschel, National Education Policy Center, Understanding and Improving Full-Time Virtual Schools: A Study of Student Characteristics, School Finance, and Student Performance in Schools Operated by K12 Inc., organizational report, July 2012.

- Center for Public Education, Searching for the Reality of Virtual Schools, organizational report, May 2012.

- Stephanie Saul, Profits and Questions at Online Charter Schools, New York Times, December 12, 2011.

- Lee Fang, How Online Learning Companies Bought America's Schools, The Nation, December 5, 2011.

- Gene V. Glass and Kevin G. Welner, National Education Policy Center, Online K-12 Schooling in the U.S.: Uncertain Private Ventures in Need of Public Regulation, organizational report, October 2011.

- Burt Hubbard and Nancy Mitchell, Online K-12 Schools Failing Students but Keeping Tax Dollars, iNews Network (Rocky Mountain PBS), September 27, 2011.

- Julie Underwood, ALEC Exposed: Starving Public Schools (sub. req'd.), The Nation, July 12, 2011.

- Center for Research on Education Outcomes, Charter School Performance in Pennsylvania, organizational report, April 4, 2011.

Related SourceWatch Articles

- Connections Academy

- Outsourcing America Exposed Portal

- American Legislative Exchange Council

- Foundation for Excellence in Education

Related PRWatch Articles

- Dustin Beilke, K12 Inc. Tries to Pivot from Virtual School Failures to Profit from "Non-Managed" Schools, PRWatch, January 7, 2016.

- Mary Bottari, From Junk Bonds to Junk Schools: Cyber Schools Fleece Taxpayers for Phantom Students and Failing Grades, PRWatch, October 2, 2013.

- Lisa Graves, ALECexposed: List of Corporations and Special Interests that Underwrote ALEC's 40th Anniversary Meeting, PRWatch, August 15, 2013.

- Brendan Fischer, Cashing in on Kids: 139 ALEC Bills in 2013 Promote a Private, For-Profit Education Model, PRWatch, July 16, 2013.

- Lisa Graves, Taxpayer-Enriched Companies Back Jeb Bush's Foundation for Excellence in Education, Its Buddy ALEC, and Their 'Reforms', PRWatch, November 28, 2012.

External Articles

- Stephanie Simon, "Online schools face backlash as states question results," Reuters, October 3, 2012.

- Forces behind the privatization of education, Workers World, May 17, 2012.

- Rhania Khalek, Why Is Public Education Being Outsourced to Online Charter Schools?, Alternet, January 8, 2012.

References

- ↑ Fuel Education, homepage, organizational website, accessed July 24, 2014.

- ↑ Sean Cavanaugh, "K12 Inc. Building a New Identity for Part of the Company," Education Week, April 4, 2014. Accessed July 24, 2014.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 K12 Inc., 2014 Annual Report, K12 Inc., 2015.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Dustin Beilke, "K12 Inc. Tries to Pivot from Virtual School Failures to Profit from 'Non-Managed' Schools," Center for Media and Democracy, PR Watch, January 7, 2016.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Lisa Graves, Taxpayer Enriched Companies Back Jeb Bush's Foundation for Excellence in Education, Its Buddy ALEC, and Their 'Reforms', PRWatch, November 28, 2012.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 K12 Inc., S-1 Registration Statement, corporate SEC filing, July 27, 2007.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 David K. Randall, Virtual Schools, Real Businesses, Forbes, July 24, 2008.

- ↑ Daniel Golden, Former Secretary of Education Plans School on Internet (sub. req'd., excerpted here), Wall Street Journal, December 28, 2000.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 National Education Policy Center, Virtual Schools in the U.S. 2013: Politics, Performance, Policy, and Research Evidence, organizational report, Alex Molnar, ed., May 2013.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 K12 Inc., 2013 Annual Report/Form 10-K, corporate annual report filed with the SEC, August 29, 2013.

- ↑ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 11.11 Stephanie Saul, Profits and Questions at Online Charter Schools, New York Times, December 12, 2011.

- ↑ Victor Reklaitis, Tilson: Biggest Short Is Ed-tech Firm K12 Inc., MarketWatch Pulse, September 17, 2013.

- ↑ Whitney Tilson, An Analysis Of K12 And Why It Is My Largest Short Position, Seeking Alpha, September 22, 2013.

- ↑ Whitney Tilson, An Analysis of K12 and Why it is my Largest Short Position, investment presentation at Value Investing Congress in New York, September 17, 2013.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Trevor Aaronson and John O'Connor, Florida Investigates K12, Nation's Largest Online Educator, State Impact (NPR), September 11, 2012.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 National Education Policy Center, A Study of Student Characteristics, School Finance, and School Performance in Schools Operated by K12 Inc., organizational report, July 2012.

- ↑ Lyndsey Layton and Emma Brown, Virtual schools are multiplying, but some question their educational value, Washington Post, November 26, 2011.

- ↑ Lyndsey Layton, Study raises questions about virtual schools, Washington Post, October 24, 2011.

- ↑ Annys Shin, Bennett Quits K12 Board After Remarks, Washington Post, October 4, 2005.

- ↑ National Conference of State Legislatures, Education Bill Tracking Database, organizational database, accessed September 2013.

- ↑ Center for Research on Education Outcomes, Charter School Performance in Pennsylvania, organizational report, April 4, 2011, p. 20.

- ↑ Burt Hubbard and Nancy Mitchell, Online K-12 Schools Failing Students but Keeping Tax Dollars, iNews Network (Rocky Mountain PBS), September 27, 2011.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 Stephanie Simon, Cyber schools flunk, but tax money keeps flowing, Politico, September 26, 2013.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 Marc Sternberg and Marc Holley, "Walton Family Foundation: We Must Rethink Online Learning", Education Weekly, January 26, 2016.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Steven Rosenfeld, "Online Public Schools Are a Disaster, Admits Billionaire, Charter School-Promoter Walton Family Foundation", Alternet, February 11, 2016.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Chas Sisk, Tennessee Virtual Academy hits bottom, gets reprieve, The Tennesseean, August 25, 2013.

- ↑ Grace Hood, Institute to Reject Colorado Virtual Academy Application, Ripples Felt on Wall Street, KUNC 91.5 Community Radio for Northern Colorado, November 20, 2012.

- ↑ Leanne Emm, Assistant Commissioner, Colorado Department of Education, Adams County School District Audit for 2008-2009 and 2009-2010 School Years, state agency financial audit, April 26, 2011.

- ↑ Burt Hubbard and Nancy Mitchell, Online K-12 Schools Failing Students but Keeping Tax Dollars, iNews Network (Rocky Mountain PBS), September 27, 2011.

- ↑ Evergreen Education Group, Data & Information: Pennsylvania, consulting firm website, accessed September 2013.

- ↑ Pennsylvania, Act 88, state legislation, approved June 29, 2002.

- ↑ Reach Foundation, Cyber Charter Schools, organizational website, accessed September 2013.

- ↑ Pennsylvania General Assembly, Bill Information: Regular Session 2001-2002: House Bill 4, state legislative website, accessed September 2013.

- ↑ Debra Erdley, Pennsylvania officials: Expand oversight of cyber education, TribLIVE, August 24, 2013.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 Benjamin Herold, K12 Inc. Sued Over For-Profit Education Company's Tax-Subsidized Funding Manipulation, Huffington Post, January 23, 2013.

- ↑ Center for Research on Education Outcomes, Charter School Performance in Pennsylvania, organizational report, April 4, 2011, p. 20.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Eric Litke, Gannett Wisconsin Media Investigative Team, Virtual schools dropping for-profit vendors, Green Bay Press Gazette, August 27, 2012.

- ↑ California Department of Justice, Attorney General Kamala D. Harris Announces $168.5 Million Settlement with K12 Inc., a For-Profit Online Charter School Operator, California Department of Justice, July 8, 2016.

- ↑ Benjamin Herold, Ex-workers claim operator of cyber-charters played games with enrollment figures, NewsWorks, January 21, 2013.

- ↑ Interview with Center for Media and Democracy, September 30, 2013.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 42.4 42.5 Benjamin Herold, Ex-workers claim operator of cyber-charters played games with enrollment figures, NewsWorks, January 21, 2013.

- ↑ Leanne Emm, Assistant Commissioner, Colorado Department of Education, Adams County School District Audit for 2008-2009 and 2009-2010 School Years, state agency financial audit, April 26, 2011.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Sean Cavanagh, K12 Inc. Reaches Tentative Settlement in Investor Lawsuit, Education Week, March 5, 2013.

- ↑ Allie Gross, "Lawsuit accuses K12 Inc., former CEO of misleading investors," Education Dive, April 15, 2014. Accessed July 24, 2014.

- ↑ Michele Molnar, "NCAA Bans Coursework Completed by Athletes in 24 K12 Inc. Virtual Schools," Education Week, April 23, 2014. Accessed July 24, 2014.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Greg Toppo, Online schools spend millions to attract students, USA Today, November 28, 2012.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Trevor Aaronson and John O'Connor, Internal Recording Reveals K12 Inc. Struggled to Comply With Florida Law, State Impact (NPR), May 12, 2013.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Sean Cavanagh, Florida Investigation Faults K12 Inc. for Teaching Assignments, Education Week, April 25, 2013.

- ↑ Jessica Calefati, Newark charter school contract with K12 Inc. shows influence of for-profit companies in public schools, The Star-Ledger, September 17, 2013.

- ↑ Whitney Tilson, An Analysis of K12 (LRN) and Why It is My Largest Short Position, Value Investing Congress, September 17, 2013.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 John O'Connor, Georgia Threatens To Close K12-run Online Charter School, State Impact (NPR), November 26, 2012. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "GA" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ American Legislative Exchange Council, "ALEC Personnel Directory," organizational document, September 13, 1985. Archived by Legacy Tobacco Documents Library, University of California-San Francisco, accessed August 2015.

- ↑ Samuel Brunelli, "Letter to Samuel Chilcote," correspondence, September 7, 1989. Archived by Legacy Tobacco Documents Library, University of California-San Francisco, accessed August 2015.

- ↑ American Legislative Exchange Council, "News Clips on ALEC's 'Making the Grade: The Report Card on American Education,'" organizational document, September 10, 1993. Archived by Legacy Tobacco Documents Library, University of California-San Francisco, accessed August 2015.

- ↑ Samuel A. Brunelli, "ALEC's 21st Annual Meeting," correspondence, June 23, 1994. Archived by Legacy Tobacco Documents Library, University of California-San Francisco, accessed August 2015.

- ↑ American Legislative Exchange Council, Inside ALEC Jul. 2009, organization newsletter, July 2009, p. 15, on file with CMD.

- ↑ Brendan Fischer, Cashing in on Kids: 139 ALEC Bills in 2013 Promote a Private, For-Profit Education Model, PRWatch, July 16, 2013.

- ↑ American Legislative Exchange Council, Education Task Force Directory, organizational task force membership directory, July 1, 2011, p. 35, obtained and released by Common Cause April 2012.

- ↑ American Legislative Exchange Council, May 2011 ALEC Education Task Force Meeting materials, organizational document, March 31, 2011, obtained and released by Common Cause April 2012.

- ↑ American Legislative Exchange Council, "Solutions for the States," 38th Annual Meeting agenda, on file with CMD, August 3-6, 2011

- ↑ Lisa Graves, ALECexposed: List of Corporations and Special Interests that Underwrote ALEC's 40th Anniversary Meeting, PRWatch, August 15, 2013.

- ↑ Nick Surgey, "ExxonMobil Top Sponsor at ALEC Annual Meeting," Exposed by CMD, Center for Media and Democracy, July 27, 2016.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Center for Media and Democracy, ALEC at 40: Turning Back the Clock on Prosperity and Progress, organizational report, August 2013, p. 25.

- ↑ American Legislative Exchange Council, Education Task Force: News: Task Force Meeting December 4, 2004, organizational website, archived by the Wayback Machine on February 4, 2005.

- ↑ American Legislative Exchange Council, Virtual Public Schools Act, organizational "model" legislation, approved January 2005, obtained and released by the Center for Media and Democracy July 2011, accessed September 2013.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 67.2 In the Public Interest, Profiting from Public Dollars: How ALEC and Its Members Promote Privatization of Government Services and Assets, September 2012.

- ↑ Bill Moyers, The United States of ALEC, September 28, 2012

- ↑ Gail Collins, Virtually Educated, New York Times, December 2, 2011

- ↑ In the Public Interest, Corporate Interests Pay to Play to Shape Education Policy, Reap profits: Emails Show Bush-Led Organization's ALEC-Like Role in State Policymaking, organizational publication, January 30, 2013.

- ↑ Lisa Graves, Taxpayer-Enriched Companies Back Jeb Bush's Foundation for Excellence in Education, its Buddy ALEC, and Their "Reforms", PRWatch, November 28, 2012.

- ↑ Donald Cohen, In the Public Interest, Bush's Education Nonprofit and Corporate Profits, organizational publication, January 30, 2013.

- ↑ Center for Responsive Politics, Client Profile: Summary, 2014, Open Secrets, 2015.

- ↑ National Institute on Money in State Politics, Noteworthy Contributor Summary: K12 Inc, FollowTheMoney state political influence database, accessed July 2013.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 75.2 Motoko Rich, Georgia's Voters Will Decide on Future of Charter Schools, New York Times, November 5, 2012.

- ↑ National Institute on Money in State Politics, Families for Better Public Schools, FollowTheMoney state political influence database, accessed July 2013.

- ↑ National Institute on Money in State Politics, Client Summary: K12 Inc., FollowTheMoney state political influence database, accessed September 2013.

- ↑ National Money in State Politics, Lobbyist Link: Client Summary: K12 Inc., FollowTheMoney state political influence database, accessed September 2013.

- ↑ K12 Inc., Nathaniel A. Davis, organizational biography, accessed July 24, 2014.

- ↑ Nathaniel A. Davis, Bloomberg Businessweek, profile, accessed July 24, 2014.

- ↑ Lyndsey Layton and Emma Brown, Virtual schools are multiplying, but some question their educational value, Washington Post, November 26, 2011.

- ↑ Ronald Packard, Forbes profile, accessed September 2013.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 K12 Inc., 2013 DEF 14A Proxy Statement, SEC filing, October 28, 2013, p. 39.

- ↑ K12 Inc., 2013 DEF 14A Proxy Statement, SEC filing, October 28, 2013, p. 14.

- ↑ Morningstar, “K12 Inc., 2013 Executive Compensation, Ronald J. Packard/Chief Executive Officer,” figures for 2009-2013, accessed November 19, 2013.

- ↑ K12 Inc., 2013 DEF 14A Proxy Statement, SEC filing, October 28, 2013, p. 16.

- ↑ “K12 Inc. Overview, Market Cap," Wall Street Journal MarketWatch, accessed September 23, 2013.

- ↑ "Ronald Packard: At a Glance," Forbes, accessed September 17, 2013

- ↑ Safanad and Ron Packard, Founder of K12 Inc., Launch Pansophic Learning and Acquire Assets from K12 to Pursue Global Education Opportunities," press release, June 13, 2014. Accessed July 24, 2014.

- ↑ K12 Inc., "K12 Inc. and Safanad Limited Announce Intent to Create New Company Led by Ron Packard," press release, January 7, 2014. Accessed July 24, 2014.

- ↑ Catherine Ho, "K12 founder Ron Packard steps down to start new online education venture," Washington Post, January 8, 2014. Accessed July 24, 2014.

- ↑ Daniel Golden, "Former Secretary of Education Plans School on Internet," The Wall Street Journal, December 28, 2000, accessed September 17, 2013.

- ↑ "In Brief," The Washington Post, April 4, 2003, accessed September 4, 2013.

- ↑ Ty McMahan, "Constellation Ventures Stays Course After Bear Stearns Meltdown," The Wall Street Journal, May 4, 2009, accessed September 4, 2013.

- ↑ Kate Kelly, Liam Pleven and James R. Hagerty, "Wall Street, Bear Stearns Hit Again By Investors Fleeing Mortgage Sector," The Wall Street Journal, August 1, 2007, accessed September 12, 2013.

- ↑ William D. Cohan, House of Cards: A Tale of Hubris and Wretched Excess on Wall Street (New York: Doubleday, 2009).

- ↑ John Hechinger, "Education According to Mike Milken,” Bloomberg BusinessWeek, June 2, 2011, accessed September 19, 2013.

- ↑ Lee Fang, "How Online Learning Companies Bought America's Schools," The Nation, November 16, 2011, accessed September 9, 2013.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 Srana Mitra, “A Scalable K-12 Education Solution: K12 CEO Ron Packard (Part 1)," interview with Ron Packard, November 18, 2009, accessed September 12, 2013.

- ↑ Marquis Biographies Online, "Profile Detail: Ronald J. Packard," accessed September 10, 2013.

- ↑ Daniel Golden, "Former Secretary of Education Plans School on Internet," The Wall Street Journal, December 28, 2000, accessed September 17, 2013.

- ↑ "Ronald Packard," bio at the Chicago Booth School's “Distinguished Alumni Awards” website, accessed September 12, 2013.

- ↑ "Executive Profile: Ronald J. Packard CFA," Bloomberg BusinessWeek, accessed September 12, 2013.

- ↑ Emma Brown, "Shareholder Lawsuit Accuses K12 Inc. of Misleading Investors," The Washington Post, January 31, 2012, accessed September 19, 2013.

- ↑ United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, Hoppaugh v. K12, Inc., Case No. 1:12-CV-103-CMH-IDD, pp. 104-105., accessed September 17, 2013.

- ↑ Kristin Jones, "[1] K12 Agrees to $6.75 Million Payment to Settle Disclosure Suit]," The Wall Street Journal, March 4, 2013, accessed September 11, 2013.

- ↑ Labaton Sucharow, "[2] In re K12 Inc. Securities Litigation]," accessed September 11, 2013.

- ↑ American Legislative Exchange Council, "Education Task Force," organizational web page, archived by the "WayBack Machine" September 28, 2006.

- ↑ Jeanne Allen, "Here They Go Again…," Center for Education Reform website, accessed September 6, 2013.

- ↑ Digital Learning Now (a project of the Foundation for Excellence in Education), "Digital Learning Council," organizational website, accessed September 9, 2013.

- ↑ Foundation For Excellence in Education, "Meet Our Donors," organizational website, accessed September 9, 2013.