Colorado and fracking

|

This article is part of the FrackSwarm portal on SourceWatch, a project of Global Energy Monitor and the Center for Media and Democracy. To search by topic or location, click here. |

| This article is part of the FrackSwarm coverage of fracking. | |

| Sub-articles: | |

| Related articles: | |

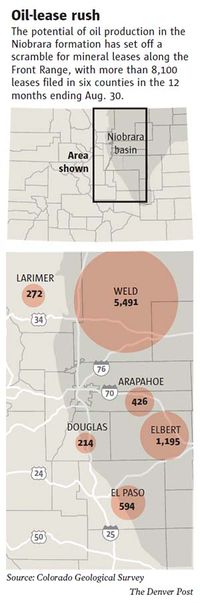

The number of active oil and gas wells in Colorado almost doubled from 22,228 in 2000 to 43,354 in 2010. Analysts believe there is more oil shale and shale gas to be found in the state.[1] Pushing the lease growth is the discovery of oil in the Niobrara shale, which sits more than 6,000 feet below the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains. The oil is not uniformly distributed in the vast shale and limestone formation, which stretches from southern Colorado into Wyoming.[2]

As of 2015 Colorado had 3,485 oil and gas operators.[3]

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Drilling wells

- 3 Injection wells

- 4 Environmental and Health Impacts

- 5 Regulations and oversight

- 6 Fracking studies

- 7 Fracking accidents

- 8 Statewide citizen activism

- 9 Local/regional citizen activism

- 9.1 Pawnee National Grassland

- 9.2 Lafayette

- 9.3 Boulder

- 9.4 Fort Collins

- 9.5 Broomfield

- 9.6 El Paso County moratorium

- 9.7 Loveland considers water ban for fracking

- 9.8 Colorado Springs group sues to allow vote on fracking ban

- 9.9 Residents meet in Windsor to discuss fracking impacts

- 9.10 Citizens march to deliver signatures opposing fracking operation

- 9.11 Public Trust Initiatives

- 9.12 Voters in four Colorado cities call for timeout on fracking

- 9.13 Compromise made over fracking measures

- 9.14 Thornton

- 10 Citizen groups

- 11 Industry groups

- 12 Reports

- 13 Resources

Introduction

According to the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), 95 percent of new wells in Colorado use fracking to access the natural gas. The BLM states that, in Colorado, the majority of fluids used in the fracturing process are recycled and no fluids are sent to wastewater treatment plants, which has caused water quality concerns in the eastern United States. For the fluids disposed of, the BLM states that 60 percent goes into "deep and closely-regulated" waste injection wells, 20 percent "evaporates from lined pits" and 20 percent is "discharged as usable surface water" under permits from the Colorado Water Quality Control Commission.[4]

The Bureau of Labor Statistics and U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis said in 2009 that the natural gas industry represented 7.3% of Colorado’s economy.[5] According to industry data, at least 430 million gallons of chemical-laced fluids have been injected into more than 9,000 oil and gas wells in the state, mostly along the northern Front Range and the Western Slope.[6]

Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper (D) is a former petroleum geologist for Buckhorn Petroleum. Hickenlooper took $75,000 from oil and gas interests in his 2010 election, and appointed an industry campaign donor to an important regulatory position. He has appeared in industry-funded ads in newspapers and on radio stations across the state, proclaiming that no water in Colorado had been contaminated by fracking, and has said that fracking fluids are edible.[7]

Drilling wells

Gas and oil leases in six Colorado counties — Larimer, Weld, Arapahoe, Douglas, Elbert and El Paso — more than doubled between 2008 and 2011, with 8,100 leases filed from August 2010 to August 2011, according to county records. Leases were granted to 40 different companies. If Weld County, a traditional oil and gas area, is removed, leasing activity jumped to 2,700 leases in 2010-2011, from 117 in the same period in 2008-09. According to the Denver Post, "Propelling the rush is the discovery of oil in the Niobrara — a geological formation sitting more than 6,000 feet below the Front Range."[2]

Proposed projects

In August 2012, about 30,000 acres will be put up for lease for oil & gas drilling near the North Fork Valley communities of Hotchkiss, Paonia, and Crawford, Colorado. The Bureau of Land Management released a March 2012 Draft Preliminary Environmental Assessment and announced a Finding of No Significant Impact. The finding was based on two old guidance documents: a 1989 Resource Management Plan and a 1987 Report on Oil & Gas. Critics say oil & gas has changed a lot over the years, particularly the growth of fracking, and more is known today about possible health risks, with BLM currently working on new guidance documents. They say a detailed Environmental Impact Statement is needed for the decision, particularly since the parcels being considered are near Paonia Reservoir, Fire Mountain Canal, Cottonwood Creek and other critical waterways.[8]

In fall 2018, just weeks before an election with minimum fracking distance requirements on the ballot, Highlands Natural Resources Corporation, an English and Scottish outfit, filed paperwork for 31 wells using four drilling pads in the area of Rocky Flats and Standley Lake[9], with plans to file for additional applications. A county map suggests that intent is actually for 109 wells on 16 pads.

The 2010 top drillers and number of permits in Colorado

The top drillers and number of permits in Colorado for the 12-month period ending August 30, 2011:[2]

Weld County

Mineral Resources: 1,018

EOG Resources: 594

Diamond Resources: 483

Larimer County

Marathon Oil: 50

Strata Oil & Gas: 45

Prospect Energy: 44

Arapahoe County

GFL & Associates: 137

Chesapeake Exploration: 82

Upstream Innovations: 56

Douglas County

Chesapeake Exploration: 103

Meredith Land & Minerals: 55

Great Western Oil & Gas: 16

Elbert County

Chesapeake Exploration: 411

ConocoPhillips: 162

Continental Land Resources: 155

El Paso County

Transcontinent Oil: 138

Continental Land Resources: 110

Simmons-McCartney: 94

Gothic Shale

Bill Barrett Corporation has drilled and completed several gas wells in Colorado's section of the Gothic shale. The wells are in Montezuma County, Colorado, in the southeast part of the Paradox basin. A horizontal well in the Gothic flowed 5,700 MCF per day.[10]

Niobrara Shale

The Niobrara shale is a shale rock formation located in Northeast Colorado, Northwest Kansas, Southwest Nebraska, and Southeast Wyoming. Oil as well as natural gas can be found deep below the earth's surface at depths of 3,000 - 14,000 feet. Fracking is used to extract these natural resources.

The Niobrara Shale is located in the Denver–Julesburg basin which is often refered to as the DJ Basin. This oil shale play is being compared to North Dakota's Bakken formation. Oil & Gas companies are quickly leasing land in the core zones located in Weld County Colorado, Yuma County Colorado, and even Cheyenne, Kansas.[11]

Public lands

The Colorado Independent reported in 2015 Colorado BLM conducts oil and gas lease sales four times per year.[12]

The Colorado Bureau of Land Management plans to auction off 12,000 acres of public lands for oil and gas drilling in November 2013. Most of the acres are located less than ten miles from the state park of Mesa Verde.[13]

In November 2015 the Bureau of Land Management office put up for auction 90,000 acres of mineral rights for drilling. Much of the land was within the Pawnee National Grassland. Buyers had purchased 93 percent. The average bid was less than $60 per acre. The sale made $5,021,931.[14]

Injection wells

Earthquakes

Colorado has about 305 disposal wells and two or three sets of earthquakes in the state have been linked to injection wells, although none definitively since the early 2000s. One of the earliest known cases of “induced seismicity” from wastewater injection occurred at the Rocky Mountain Arsenal in 1966, linked to a well designed to dispose of tainted water from the chemical weapons site. More recently, a series of small earthquakes near Trinidad may have been related to drilling injection wells.[15]

In 2011, the oil and gas commission began requiring a site review by the Colorado Geological Survey to look for proximity to known faults before permitting injection wells. The commission also limits the injection pressures for the wells to prevent fractures and limits the total volume of wastewater pumped down the wells.[15]

The U.S. Geological Survey linked a 2011, 5.3-magnitude earthquake near New Mexico to hydraulic fracturing and wastewater disposal. The U.S. Geological Survey has warned that earthquakes are 100 times more likely to occur now than in 2008 in fracking and wastewater disposal areas.[16]

In April 2013, it was reported that an ongoing earthquake swarm in New Mexico and Colorado, which includes Colorado's largest earthquake since 1967, was due to underground wastewater injection, researchers said at the Seismological Society of America's annual meeting in Salt Lake City. The reported earthquakes are concentrated near wastewater injection wells in the Raton Basin. Companies there have been extracting methane from underground coalbeds. The basin stretches from northeastern New Mexico to southern Colorado.[17]

In Greeley, Colorado, June 2014 researchers installed several seismometers nearby an a recent earthquake. Seismometers identified the injection well that caused the quake. About 300,000 barrels a month were injected into the well. The waste water injection was still causing tremors. Colorado regulators temporarily shut down the well and lowered its rate of injection.[18]

The state assembly began 2016 by discussing a proposal to hold oil and gas companies liable for earthquakes.[19]

Waste Exemptions

A 2012 ProPublica investigation into the threat to water supplies from underground injection of waste found the EPA has granted energy and mining companies exemptions to release toxic material in more than 1,500 places in aquifers across the country. The EPA may issue exemptions if aquifers are too remote, too dirty, or too deep to supply affordable drinking water; however, EPA documents showed the agency has issued permits for portions of reservoirs that are in use, assuming contaminants will stay within the finite area exempted. More than 1,100 aquifer exemptions have been approved by the EPA's Rocky Mountain regional office, according to a list the agency provided to ProPublica. Many of them are relatively shallow and some are in the same geologic formations containing aquifers used by Denver metro residents. More than a dozen exemptions are in waters that might not be treated before supplied as drinking water.[20]

Environmental and Health Impacts

Water use

The 2013 Western Organization of Resource Councils report, "Gone for good: Fracking and water loss in the West," found that fracking is using 7 billion gallons of water a year in four western states: Wyoming, Colorado, Montana, and North Dakota.

State officials charged with promoting and regulating the energy industry estimated that fracking required about 13,900 acre-feet of water in 2010, about 0.08 percent of the total water consumed in Colorado. A Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission report projected water needs for fracking will increase to 18,700 acre-feet a year by 2015. Environmentalists point out that the water used by fracking gets lost from the hydrological cycle forever because it is contaminated.[21]

Several projects in the state have proposed draining water out of Colorado rivers and siphoning the water to towns and cities that have been selling large quantities for fracking. Environmental advocates note that fracking in Colorado could negatively impact the state's rivers, as the process requires a significant amount of water.[22]

As of 2012, water-intensive fracking projects includes:[23]

- the Windy Gap Firming Project, which proposes to drain up to an additional 10 billion gallons of water out of the Upper Colorado River every year and pipe and pump that water to northern Front Range Colorado cities including Loveland, Longmont and Greeley -- three cities that have recently started selling water for fracking (Greeley sold over 500 million gallons in 2011).

- the Northern Integrated Supply Project, which proposes to drain an additional 13 billion gallons per year out of the Cache la Poudre River northwest of Fort Collins.

- the Seaman Reservoir Project by the City of Greeley on the North Fork of the Cache la Poudre River, which proposes to drain several thousand acre feet of water out of the North Fork and the mainstem of the Cache la Poudre.

- the Flaming Gorge Pipeline, which could reportedly take a large amount of water—up to 81 billion gallons—out of the Green and Colorado River systems every year and pipe and pump that water to the Front Range.

- the City of Denver has opened up drilling and fracking on its property at Denver International Airport, while Denver is also pushing forward with the Moffat Collection System Project, a proposal to drain water out of the Upper Colorado River and pipe it to Denver.

In March 2012 at Colorado's auction for unallocated water, companies that provide water for hydraulic fracturing at well sites were top bidders on supplies once claimed exclusively by farmers. The Northern Water Conservancy District runs the auction, offering excess water diverted from the Colorado River Basin — 25,000 acre-feet so far this year — and conveyed through a 13-mile tunnel under the Continental Divide. The average price paid for water at the auctions has subsequently increased from around $22 an acre-foot in 2010 to $28 in 2012.[24] In June 2012, the town of Erie doubled its commercial water rate from $5.73 per 1,000 gallons to $11.46 per 1,000 gallons -- for oil and gas developers only.[25]

About 98 percent of the state is experiencing varying levels of drought in 2012, according to the Colorado State University (CSU), with the most severe in the Arkansas Basin, where drought levels range from D1, or "moderate," to D3, or "extreme." The Texas drought from summer 2011 is also still affecting Colorado, CSU said.[26]

On July 9, 2012, the Aurora City Council in CO voted to "lease" water to Houston-based Anadarko Petroleum, which will use the water for hydraulic fracturing. Anadarko will pay the city $9.5 million over five years for access to almost 2.5 billion gallons of water.[27]

Water contamination

A 2013 study published in Endocrinology - "Estrogen and Androgen Receptor Activities of Hydraulic Fracturing Chemicals and Surface and Ground Water in a Drilling-Dense Region" - found water samples near Colorado gas drilling in Garfield County using hydraulic fracturing showed the presence of chemicals linked to infertility, birth defects, and cancer, at higher levels than areas where fracking was not taking place. The study also found elevated levels of the hormone-disrupting chemicals in the Colorado River, where wastewater released during accidental spills at nearby wells could wind up.

Spills

An analysis by Environmental Working Group and The Endocrine Disruption Exchange (TEDX) found that at least 65 chemicals used by natural gas companies in Colorado are listed as hazardous under six major federal laws designed to protect Americans from toxic substances.[6]

In 2004, Canada-based Encana Corp. improperly cemented and hydraulically fractured a well in Garfield County, Colorado. The state found that the poor cementing caused natural gas and associated contaminants to travel underground more than 4,000 feet laterally. As a result, a creek became contaminated with dangerous levels of carcinogenic benzene. The state of Colorado fined Encana a then-record $371,200. After more than seven years of cleanup efforts, as of September 2012, three groundwater monitoring wells near the creek still showed unsafe levels of benzene.[28][29]

In 2008, a drilling wastewater pit in Colorado leaked 1.6 million gallons of fluid, which migrated into the Colorado River.[30]

A 2008-2011 Colorado School of Public Health hydrological study found that as the number of gas wells in Garfield County increased, methane levels in water wells also rose. State regulators later fined EnCana Oil and Gas for faulty well casings that allowed methane to migrate into water supplies through natural faults.[31][32]

In 2009, a wastewater spill flowed into a tributary of Dry Creek in Garfield County. It took almost a month for Antero Resources to notify regulators. [33]

During an eight-month period in 2011, companies in the state spilled 2 million gallons of fluids. Officials say there are up to 400 oil and gas spills each year in Colorado, but that only 20 percent contaminate groundwater.[34]

In 2010, a land owner observed an odor in water seeping from a gravel pit west of Silt in Garfield County. A pipeline carrying wastewater from 36 wells on five well pads in the Colorado River floodplain had leaked and contaminated groundwater. The farmer reported that he used the water for a year after the pipeline was installed. It is unknown when the leak started. Water sampling revealed high levels of benzene, toluene and total xylenes. In May 2013 the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission fined Antero Resources $150,000 for the spill. The owner used water from the pit for crop irrigation and sometimes disposed of it in the Colorado River.[35]

In March 2013 it was reported that an "underground plume of toxic hydrocarbons from an oil spill north of the Colorado River near Parachute [Colorado] has been spreading for 10 days, threatening to contaminate spring runoff. Vacuum trucks have sucked up more than 60,000 gallons, but an unknown amount remains in the ground by Parachute Creek," which flows into the Colorado River.[36] The company responsible for the leak, Williams Energy, was put in charge of the clean-up.[37]

The leak was caused by a faulty pressure gauge on a four-inch pipeline. Benzene levels in Parachute Creek rose above the safety threshold of 5 parts per billion. Following the spill, Colorado lawmakers discovered that state penalties for such accidents had been capped at $10,000 since the 1960s. In response, they passed legislation in May 2013 that increased possible state fines for such incidents. But the state had yet to fine Williams Energy.[37]

Floods of 2013

During the massive floods in Colorado in September 2013, sites that employed the use of fracking were flooded. It was reported that "These floods have not only overwhelmed roads and homes, but also the oil and gas infrastructure stationed in one of the most densely drilled areas in the U.S. Although oil companies have shut down much of their operations in Weld County due to flooding, nearby locals say an unknown amount of chemicals has leaked out and possibly contaminated waters, mixing fracking fluids and oil along with sewage, gasoline, and agriculture pesticides ... No one, from oil companies to regulators, seems to know the exact extent of the damage yet as they survey the damage. But Executive Director of the Colorado Department of Natural Resources Mike King told the Denver Post that, 'The scale is unprecedented.' Meanwhile, the Colorado Department of Public Health has advised everyone to stay away from the water, as it is possibly contaminated by 'raw sewage, as well as potential releases from homes, businesses, and industry.' Two of the region’s largest oil and gas companies, Encana and Anadarko, said they responded by shutting-in or closing down several hundred of their wells, a precaution until they assess the full damage."[38]

Shortly after flooding receded there were reports of two large spills and eight minor ones. Anadarko Petroleum reported the two larger releases in Weld County. About 125 barrels — or 5,250gallons — spilled into the South Platte River near Milliken. A tank farm on the St. Vrain River released 323 barrels — or 13,500 gallons — near Platteville. The state oil and gas commission said it is trying to compile a comprehensive list of facilities in the flooded areas and their status, including what chemicals they had on site.[39][40]

Air

Oil and gas industry sources emit at least 600 tons of contaminants in the state a day, as of 2013. They are the main source of volatile organic compounds in Colorado and the third-largest source of nitrogen oxides. A nine-county area around metro Denver does not meet federal clean-air standards, according to state data.[41]

Health effects

A study conducted over three years by the Colorado School of Public Health concluded that fracking can contribute to “acute and chronic health problems for those living near natural gas drilling sites”. The report will be published in Science of the Total Environment. "The study found those living within a half-mile of a natural gas drilling site faced greater health risks than those who live farther away." Researchers located “potentially toxic petroleum hydrocarbons in the air near the wells including benzene, ethylbenzene, toluene and xylene.” Benzene is classified as a known carcinogen by the EPA.

Researchers collected data in Garfield County, CO from January 2008 to November 2010, using EPA air quality standards. The study reiterates earlier research which shows that prolonged exposure to airborne petroleum hydrocarbons causes “an increased risk of eye irritation and headaches, asthma symptoms, acute childhood leukemia, acute myelogenous leukemia, and multiple myeloma.”[42]

Methane

A 2012 study published in the Journal of Geophysical Research and led by researchers at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the University of Colorado, Boulder, estimated that natural-gas producers in an area known as the Denver-Julesburg Basin in Colorado are losing about 4% of their natural gas to the atmosphere — not including additional losses in the pipeline and distribution system. This is more than double the official inventory of methane leakage.[43]

Ozone

According to the state of Colorado, natural gas and oil operations were the largest source of ozone-forming pollution, VOCs and NOx, in 2008.[44]

A 2013 Environmental Science and Technology study by scientists at the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences found that emissions from oil and natural gas operations account for 55% of the pollutants -- such as propane and butane -- that contribute to ozone formation in Erie, CO. Key to the findings was the recent discovery of a "chemical signature" that differentiates emissions by oil and gas activity from those given off by other sources.[45]

Silica

In July 2012, two federal agencies released research highlighting dangerous levels of exposure to silica sand at oil and gas well sites in five states: Colorado, Texas, North Dakota, Arkansas, and Pennsylvania. Silica is a key component used in fracking. High exposure to silica can lead to silicosis, a potentially fatal lung disease linked to cancer. Nearly 80 percent of all air samples taken by the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health showed exposure rates above federal recommendations. Nearly a third of all samples surpassed the recommended limits by 10 times or more. The results triggered a worker safety hazard alert by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.[46]

Oil and Gas Health Information and Response Program

In 2010, Colorado was the first in the nation to perform a detailed study, a “health impact assessment,” on proposed natural gas development.

In October 2015 Colorado launched the "Oil and Gas Health Information and Response Program."[1]

A PhD in toxicologist on staff. A health professional will be available to talk with citizens and their primary physicians.

Complaints can be lodged with the new program.ref>Dennis Webb, "State program for oil and gas complaints makes debut," The Daily Sentinel, November 1, 2015.</ref>

Regulations and oversight

The Colorado General Assembly created the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission to “foster the responsible development of Colorado’s oil and gas natural resources.” To do so, the COGCC developed and implemented regulations to govern the oil and gas industry. In 2010, there were more than 43,000 active wells in Colorado. That year the COGCC employed 15 inspectors, 7 who performed a total of 16,228 inspections.[47]

According to a 2015 NRDC report Colorado has less than 40 inspector for 52,198 active wells.[48]

In January 2013 the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission was set to begin a public debate over the future of fracking regulations in the state. One proposal from commission staff members would bump up the buffer between well sites and buildings from "150 feet in rural areas and 350 feet in urban areas to a flat 500 feet anywhere." Additionally, "within 1,000 feet of a building, oil and gas operators would have to notify neighbors and employ 'enhanced mitigation' measures to cut down on dust, noise, odor and lighting." It was also reported that under the new rules, "operators would have to have a hearing before the commission before proceeding with a well less than 1,000 feet away from a high-occupancy building, such as a school or hospital."[49]

Air quality rules

Colorado's Air Quality Control Commission, part of the state health department, originally aimed to have new proposed air-quality rules by November 2013, but later said they planned on extending negotiations on the air-quality rules until February 2014. Oil and gas emissions are the main source of volatile organic compounds in Colorado and the third-largest source of nitrogen oxides.[50]

Injection Wells

According to a 2015 NDRC report, between 2009 and 2013, Chevron received 53 Notice of Alleged Violations due to the safety of underground injection wells.[51]

Water testing

On January 7, 2013, Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission's (COGCC) nine-member commission unanimously voted to approve the "Statewide Groundwater Baseline Sampling and Monitoring" rule that requires oil and gas operators to collect up to four water samples from aquifers, existing water wells and other "available water sources" within a half-mile of proposed wells. The sampling must be done before wells are drilled and within 72 months after the wells are placed into operation. The rules are the first to require the oil and natural gas industry to test groundwater quality both before and after drilling.[52]

Chemical disclosure

In December 2011, in accordance with new rules brokered by Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper, energy companies in the state will have to disclose to the public the chemical family of each chemical they use in their fracking process. It has been reported that the disclosure must be made within two months on an independent internet database: FracFocus.org.[53]

The new rules require drillers to file a “notice of intent to conduct a fracking treatment” of a well 48 hours prior to a frack job, and to identify the chemicals used in a frack job within 60 days after the job is finished. Chemicals can still remain protected by trade secret designation, although that designation can be challenged by the public. Even if there are complaints, however, the COGCC is not required by the new rules to investigate, although citizens can then file a legal claim.[54][55]

Fracking studies

In a Government Accountability Office report released in July 2014, the independent oversight agency reported the "EPA’s role in overseeing the nation’s 172,000 wells, which either dispose of oil and gas waste, use 'enhanced' oil and gas production techniques, store fossil fuels for later use, or use diesel fuel to frack for gas or oil. These wells are referred to as 'class II' underground injection wells and are regulated under the Safe Drinking Water Act. Oversight of these wells vary by state, with some coming under the regulatory authority of the EPA, including the 1,865 class II wells in Pennsylvania. The GAO faults the EPA for inconsistent on-site inspections and guidance that dates back to the 1980′s. Of the more than 1800 class II wells in Pennsylvania, the GAO reports only 33 percent were inspected in 2012. Some states, including California, Colorado and North Dakota, require monthly reporting on injection pressure, volume and content of the fluid. As more oil and gas wells across the country generate more waste, the GAO highlights three new risks associated with these wells — earthquakes, high pressure in formations that may have reached their disposal limit, and fracking with diesel."[56]

Fracking accidents

In November 2014 an accident occurred at a well in northern Colorado, in which one worker was killed and two others were seriously injured. Reports stated that the "three men were trying to heat a frozen high-pressure water line when something went wrong and the line ruptured."[57]

Statewide citizen activism

In 2018, a proposed citizens' ballot initiative to limit fracking impacts was challenged by the oil and gas industry.[58] Initiative 97 met the requirements for the November 2018 elections, appearing on the ballot as Proposition 112.[59]

Local/regional citizen activism

Pawnee National Grassland

In November 2015 the Bureau of Land Management office put up for auction 90,000 acres of mineral rights for drilling. Much of the land was within the Pawnee National Grassland, located 35 miles east of Fort Collins. Outside the action protestors from multiple environmental groups protested the sale. Ninety three percent of the land was sold within three hours. [60]

Lafayette

In November 2013 Lafayette residents voted 60% to 40% for an all-out ban on new oil and gas drilling in the city.[61]

Boulder

On May 13, 2013 Boulder, Colorado moms, children and activists delivered several hundred postcards Monday to the three county commissioners before holding a rally on the Boulder County Courthouse lawn, urging the commissioners to extend a fracking moratorium. The commissioners were planning to discuss imposing transportation impact fees on oil and gas companies drilling and operating wells in the county the same week.[62]

In May 2013, the Boulder County commissioners voted 2-1 not to extend their moratorium on fracking, which will expire in June 2013. The commissioners cited the potential to get sued in their reasoning to let the ban expire.[63]

In November 2013 nearly 80 percent of Boulder residents voted in favor of a five-year extension of the city's fracking moratorium.[61]

Fort Collins

In March 2013, the Fort Collins city council passed a ban on fracking that grandfathered in the one driller, Prospect Energy, that currently operates on eight well pads in northern Fort Collins. Three weeks later, in a quiet vote without public input, the city council passed an “agreement” with the driller allowing the company to drill and frack on two new square miles of land surrounding the Budweiser brewery in North Fort Collins.[64]

In May 2013, the Fort Collins City Council overturned the fracking ban in a sharply divided 4-3 vote. The mayor pro tem cited an impending threat of a lawsuit from Prospect Energy for why he changed his vote.[65]

In November 2013 over 55 percent of Fort Collins residents voted in favor of a five-year fracking moratorium in the city.[61]

In August 2014, a Larimer County judge overturned Fort Collins' five-year moratorium on fracking. The Ft. Collins City Council has announced they are considering whether to appeal the decision.[66]

In December 2015 the Colorado Supreme Court heard arguments in two cases, Longmont's outright ban on fracking, and the Fort Collins' five-year moratorium. It is likely to take 3 months or longer for the court to make its ruling.[67]

Broomfield

The Denver suburb of Broomfield passed a five-year fracking moratorium on the by 20 votes of 20,000 cast in November 2013. In February 2014, a judge upheld the results stating that while the election had flaws it was not illegal, which some pro-fracking supporters had claimed.[68]

In summer 2017, concerned citizens launched a campaign for a citizen initiative to prioritize health and safety concerns in future oil and gas development decisions. In the fall elections, voters passed Question 301 to give the city/county “plenary authority to regulate all aspects of oil and gas development” which should “not adversely impact the health, safety and welfare” of residents, the environment or wildlife resources.

El Paso County moratorium

In September 2011, El Paso County Commission voted to impose a four-month moratorium on issuing permits for activities involving oil and gas drilling, to provide time to determine whether the Colorado county needs additional regulations on drilling.[2]

Loveland considers water ban for fracking

The City of Loveland's water utility has been selling water to suppliers of the oil and natural gas industry from metered city hydrants for use in controversial hydraulic fracturing processes to recover petroleum. In April 2012, city councilors began a process to decide whether the city will join Northern Colorado neighbors Fort Collins and Boulder in barring water sales for fracking.[69]

Longmont voters ban fracking, court overturns, appeal filed

In May 2012, the Longmont ballot issue committee Our Health, Our Future, Our Longmont filed a notice of intent with the Longmont City Clerk to put a charter amendment on the November 2012 ballot to ban hydraulic fracturing within Longmont city limits. According to Food & Water Watch, the Colorado Oil and Gas Association (COGA) and the Colorado Attorney General have tried to weaken Longmont's local regulations for oil and gas drilling, such as prohibiting drilling in residential areas, spurring the amendment. If successful, Longmont would be the first city in Colorado to ban fracking.[70]

In June 2012 the group Our Health, Our Future, Our Longmont, began a petition drive to ban fracking within city limits.[71] The ban — Ballot Question 300 — was passed by majority vote in the November 2012 election, and will amend Longmont's city charter to ban hydraulic fracturing and the storage of fracking waste in city limits.

The oil and gas industry fought the ban, giving $507,500 to the opposing group Main Street Longmont. The Colorado Supreme Court has forbidden cities from banning oil and gas drilling outright, but has decided lesser measures on a case-by-case basis. Gov. John Hickenlooper said that passage of Ballot Question 300 would likely bring a second lawsuit from the state.[72]

However, in late July 2014, a Colorado judge overturned the city's ban on fracking. Boulder County District Court Judge D.D. Mallard wrote in his decision, “While the court appreciates the Longmont citizens’ sincerely held beliefs about risks to their health and safety, the court does not find this is sufficient to completely devalue the state’s interest." Colorado Oil and Gas Association and Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation were plaintiffs in the case. Environmental groups in Colorado vowed to appeal the decision. Judge Mallard allowed the ban to remain in place while an appeal was sought.[73] In September 2014, a coalition of groups, including City of Longmont, Earthworks and Sierra Club, filed an appeal to to Judge Mallard's decision.[74]

In August 2014 the Longmont City Council voted to uphold the ban despite lawsuits filed against the city.[75] The city has accumulated more than $61,000 in legal fees defending its ban on fracking.[76]

In December 2015 Colorado Oil and Gas Association and the city of Longmont argued their case in front of the state Supreme Court.[77]

Colorado Springs group sues to allow vote on fracking ban

In May 2013 a citizens group based in Colorado Springs was reported to have "sued the city of Colorado Springs in an effort to move forward a petition to amend the City Charter to ban oil and gas drilling in the city. The Colorado Springs Citizens for Community Rights filed the lawsuit in 4th Judicial District Court in response to the city's Initiative Title Setting Review Board's refusal to affix a title to the petition. The title is needed before signatures can be gathered; the board rejected the petition, saying it violates the city's single-subject rule. The proposed charter amendment, which the group wants to see on the November ballot, would prohibit any company from engaging 'in the extraction of natural gas or oil, ' including the use of hydraulic fracturing, or fracking."[78]

Residents meet in Windsor to discuss fracking impacts

In Ocobter 2014 the group known as Windsor Community Rights Network organized an event in response to the increase of oil and gas activity in their town. Approximately 90 residents attended the educational event to learn more about potential impacts from fracking in their community.[79]

Citizens march to deliver signatures opposing fracking operation

In June 2012 a group of mothers and children living in Colorado marched into EnCana Corporation headquarters in Denver to deliver a petition signed by 21,000 people demanding the company pull the plug on its project near the town of Erie, Colorado. Encana is preparing to drill a well in Canyon Creek, where a prairie rife with birds and a wetland alive with waterfowl separate it from hundreds of houses in the nearby Creekside neighborhood. An elementary school is located a few hundreds yards south of the drilling site, which is at a legal distance.

Industry representatives dismissed the petition. A large rally was planned for June 9, 2012 to try to draw more attention to the drilling noise and pollution that burden affected citizens.[80]

Public Trust Initiatives

Phil Doe of Littleton and Richard Hamilton of Fairplay have introduced Public Trust Initiatives 3 and 45 to protect state waters. Initiative 3 would apply the common-law doctrine of “public trust” to water rights, and make “public ownership of such water legally superior to water rights, contracts, and property law.” It would also grant unrestricted public access to natural streams and their banks. Initiatives 45 would amend Article XVI, Section 6 of the state constitution to limit, and possibly prohibit, stream diversions that would “irreparably harm the public ownership interest in water.” In April 2012, the Colorado Supreme Court cleared the way for the initiatives to proceed. In order for them to appear on the November 2012 ballot, each initiative must get 86,000 signatures by August 6, 2012,[81] but they did not receive the required signatures to appear on the ballot.

Voters in four Colorado cities call for timeout on fracking

It was reported in October 2013 that four ballot measures put forth by residents of Boulder, Broomfield, Fort Collins and Lafayette, Colorado that will give voters the chance to declare timeout — and, in one case, ban new fracking projects and industry-waste disposal.[82] In November voters in the Colorado cities of Boulder, Fort Collins and Lafayette, approved antifracking initiatives by wide margins.[83]

Compromise made over fracking measures

In August 2014, Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper announced that a compromise with the oil and gas industry to keep measures off the 2014 election ballot was made. It was reported that, "U.S. Rep Jared Polis, D-Boulder, agreed to drop two measures he supported aimed at requiring drilling rigs to be set back 2,000 feet from homes and bolstering local control by adding an environmental bill of rights to the state constitution. Backers of two industry-supported measures — Initiative 121, which would have withheld state oil and gas revenue from communities banning drilling, and Initiative 137, which required a fiscal impact note for all initiatives — said they, too, would pull back."[84]

Thornton

The city of Thornton came under criticism after posting a map listing the addresses of 14 fracking opponents, and homeowners, labelled “address of interest.” In November 2015 the city removed the map.[85]

Citizen groups

- 350 Colorado

- Be The Change

- Center for Biological Diversity

- Citizens for a Healthy Community

- Citizens for Huerfano County

- Coloradans Against Fracking

- Colorado Community Rights Network

- Colorado Rising - 2018 ballot initiative campaign

- Commerce City Unite NOW (Facebook group)

- Earthjustice

- Erie Rising

- Frack Free Colorado

- Fracking Colorado

- Grand Valley Citizens Alliance

- The League of Oil and Gas Impacted Coloradans LOGIC

- Our Longmont

- Rainforest Action Network

- San Juan Citizens Alliance

- Thompson Divide Coalition

- Western Colorado Congress

Industry groups

- Advancing Colorado

- Colorado Oil & Gas Association

- Common Sense Policy Roundtable

- Environmental Policy Alliance / Big Green Radicals project - "Colorado: Ground Zero for the Hydraulic Fracturing Debate"

- Vital for Colorado - Ballotpedia info PolluterWatch info

- Western Energy Alliance

Industry actions

It was reported in October 2013 that Colorado Oil and Gas Association gave $600,000 to fight proposed fracking bans on Colorado state ballots. The trade group contributed to campaigns in Broomfield, Boulder, Lafayette and Fort Collins. [86]

A report by Colorado Ethics Watch in 2014 found that the oil industry spent $11.8 million on lobbying and elections.[87]

Front group leaders

In October 2014, Greenpeace revealed that "ex-state senator and onetime Republican gubernatorial primary candidate Josh Penry and his wife, founder of Republican PR and fundraising firm Starboard Group, Kristin Strohm" were behind "at least six oil and gas industry front groups that have been fighting state regulations designed to protect the health of its citizens and the environment." The couple also has ties to the Koch Brothers.[88]

Reports

Diesel in Fracking

From 2010 to July 2014 drillers in the state of Colorado had reported 9,173.06 gallons of diesel injected into 16 wells. The Environmental Integrity Project extensively researched diesel in fracking. The organization argues that diesel use is widely under reported.

The Environmental Integrity Project 2014 study "Fracking Beyond The Law, Despite Industry Denials Investigation Reveals Continued Use of Diesel Fuels in Hydraulic Fracturing," found that hydraulic fracturing with diesel fuel can pose a risk to drinking water and human health because diesel contains benzene, toluene, xylene, and other chemicals that have been linked to cancer and other health problems. The Environmental Integrity Project identified numerous fracking fluids with high amounts of diesel, including additives, friction reducers, emulsifiers, solvents sold by Halliburton.[89]

Due to the Halliburton loophole, the Safe Drinking Act regulates benzene containing diesel-based fluids but no other petroleum products with much higher levels of benzene.[90]

Air pollution

In a 2012 Science of the Total Environment study, researchers from the Colorado School of Public Health found that air pollution caused by hydraulic fracturing or fracking may contribute to acute and chronic health problems for those living near natural gas drilling sites. The report, based on three years of monitoring, found a number of potentially toxic and carcinogenic petroleum hydrocarbons in the air near oil/gas wells, including benzene, ethylbenzene, toluene and xylene. Benzene has been identified by the Environmental Protection Agency as a known carcinogen. Other chemicals included heptane, octane and diethylbenzene but information on their toxicity is limited. The greatest health impact corresponds to the relatively short-term, but high emission, well completion period. The effects could include eye irritation, headaches, sore throat and difficulty breathing.

The report, which looked at those living about a half-mile from the wells, was in response to the rapid expansion of natural gas development in rural Garfield County, in western Colorado - residents asked the School to test for health impacts. The lead researcher noted that "there wasn't data available on all the chemicals emitted during the well development process. If there had been, then it is entirely possible the risks would have been underestimated."[91]

Regulatory enforcement

A 2012 report by the group Earthworks, "Inadequate enforcement means current Colorado oil and gas development is irresponsible," found that the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC) has not “foster[ed] the responsible development of Colorado’s oil and gas natural resources,” its stated mission, due to its inadequate enforcement of its own rules. The report found that inspection capacity is inadequate; violations are not consistently assessed, reported, and tracked; and fines are rarely issued and are inadequate to prevent repeat violations.[92]

Resources

References

- ↑ Lisa Sumi, "Inadequate enforcement means current Colorado oil and gas development is irresponsible," Earthworks Report, March 2012.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Oil companies rushing to buy leases along Colorado's Front Range" Mark Jaffe, The Denver Post, October 23, 2011.

- ↑ Amy Mall, "Fracking's Most Wanted: Lifting the Veil on Oil and Gas Company Spills and Violations," NDRC, April 2015.

- ↑ "Fracking on BLM Colorado Well Sites" BLM, Fact Sheet, March 2011.

- ↑ "Natural Gas" COGA, accessed April 4, 2012.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 "Colorado's Chemical Injection" Dusty Horwitt, EWG Public Lands Analyst, June 2008.

- ↑ Sam Schabacker, "Hickenlooper May Be in Bed With the Oil Industry, But Coloradans Have His Wake-up Call ," HuffPo, March 12, 2012.

- ↑ "North Fork of the Gunnison," Western Colorado Congress Website, accessed March 2012.

- ↑ "350.org: Fracking Permit Applications Pending for Rocky Flats, including Superfund Sites, Standley Lake, and Surrounding Areas"

- ↑ "Barrett may haveParadox Basin discovery," Rocky Mountain Oil Journal, 14 Nov. 2008, p.1.

- ↑ "What is the Niobrara Shale Formation? " Oil and Shale Gas, February 2010.

- ↑ Kelsey Ray, "BLM auctions drilling rights to Pawnee National Grasslands," The Colorado Independent, November 15, 2015.

- ↑ Jessica Goad, "Ignoring Public Outcry, Federal Government To Offer Oil And Gas Leases Near Mesa Verde National Park," Climate Progress, July 3, 2015.

- ↑ Kelsey Ray, "BLM auctions drilling rights to Pawnee National Grasslands," The Colorado Independent, November 15, 2015.

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 Andrew Wineke, "Drilling oil takes water and makes water," The Gazette, April 28, 2012.

- ↑ "Fracking shakes the American west: a millennium’s worth of earthquakes." Joanna Walters, The Guardian, January 10, 2016.

- ↑ "New Mexico Earthquakes Linked to Wastewater Injection" Becky Oskin, Livescience.com, April 24, 2013.

- ↑ [http://www.hcn.org/issues/47.11/where-industry-makes-earthquakes "Where industry makes earthquakes Fracking has caused quakes in several states, but more research is needed."] Kindra McQuillan, High Country News, June 22, 2015.

- ↑ "Fracking shakes the American west: a millennium’s worth of earthquakes." Joanna Walters, The Guardian, January 10, 2016.

- ↑ Abrahm Lustgarten, "Poisoning the Well: How the Feds Let Industry Pollute the Nation’s Underground Water Supply," ProPublica, Dec. 11, 2012.

- ↑ Bruce Finley, "Fracking bidders top farmers at water auction," The Denver Post, April 2, 2012.

- ↑ "Will Fracking Destroy Colorado's Rivers?" Gary Wockner, Huffington Post, March 19, 2012.

- ↑ Gary Wockner, "Will Fracking Destroy Colorado’s Rivers?" EcoWatch, March 19, 2012.

- ↑ Bruce Finley, "Fracking bidders top farmers at water auction," The Denver Post, April 2, 2012.

- ↑ John Aguilar, "In Erie, oil and gas companies to pay twice as much for water," Daily Camera, June 20, 2012.

- ↑ Monte Whaley, " 98 percent of Colorado in a drought, say CSU climatologists," The Denver Post, April 3, 2012.

- ↑ Patricia Calhoun, "Fracking: Aurora votes to 'lease' water to Anadarko Petroleum," Denver Westword, July 10, 2012.

- ↑ Dusty Horwitt, "Federal Scientists Warn NY of Fracking Risks," Environmental Working Group, Feb. 22, 2012.

- ↑ Horwitt, Dusty. Senior Counsel for the Environmental Working Group. [Public testimony]. Oversight Hearing on the Revised Environmental Impact Statement on Hydraulic Fracturing and New York City’s Upstate Drinking Water Supply Infrastructure. Before the New York City Council Committee on Environmental Protection. September 22, 2011 at 2.

- ↑ Lustgarten, Abrahm, “How the West’s energy boom could threaten drinking water for 1 in 12 Americans,” ProPublica. December 21, 2008.

- ↑ Harman, Greg, “Fracking’s short, dirty history,” San Antonio (Texas) Current, January 5, 2011 -January 11, 2011.

- ↑ Smith, Jack Z., “The Barnett Shale search for facts on fracking,” Fort Worth (Texas) Star-Telegram, September 5, 2010.

- ↑ Amy Mall, "Fracking's Most Wanted: Lifting the Veil on Oil and Gas Company Spills and Violations," NDRC, April 2015.

- ↑ Colorado Public News and David O. Williams, "Cancer Concerns With Colorado's Drilling, Fracking Boom," Colorado Public News, July 21, 2013.

- ↑ Amy Mall, "Fracking's Most Wanted: Lifting the Veil on Oil and Gas Company Spills and Violations," NDRC, April 2015.

- ↑ "Parachute Creek spill continues uncontained; cause, source unknown" Denver Post, March 18, 2013.

- ↑ Jump up to: 37.0 37.1 John Upton, "Fracking accident leaks benzene into Colorado stream," Grist, May 24, 2013.

- ↑ "Colorado Floodwaters Cover Fracking And Oil Projects: ‘We Have No Idea What Those Wells Are Leaking’" Rebecca Leber, Climate Progress, September 17, 2013.

- ↑ Mark Jaffe and Bruce Finley, "State now tracking 10 oil and gas spills in Colorado flood zones," The Denver Post, Sep 19, 2013.

- ↑ "Breaking: 5,250 Gallons of Oil Spill into Colorado’s South Platte River" EcoWatch, September 19, 2013.

- ↑ Bruce Finley, "CDPHE mulls oil and gas air pollution rules as wary residents erupt," The Denver Post, July 8, 2013.

- ↑ Neela Banerjee "Study: 'Fracking' may increase air pollution health risks" LA Times, March 20, 2012.

- ↑ Jeff Tollefson, "Air sampling reveals high emissions from gas field: Methane leaks during production may offset climate benefits of natural gas," Nature, February 7, 2012.

- ↑ Elena Craft, "Do Shale Gas Activities Play A Role In Rising Ozone Levels?" Mom’s Clean Air Force, July 13, 2012.

- ↑ John Aguilr, "Study finds that more than half of ozone-forming pollutants in Erie come from drilling activity," Boulder Daily Camera, January 16, 2013.

- ↑ Adam Voge, "Fracking dust alert not shocking in Wyoming," Wyoming Star Tribune, July 30, 2012.

- ↑ "COGCC staff report," Jan. 13, 2011. p. 25.

- ↑ Amy Mall, "Fracking's Most Wanted: Lifting the Veil on Oil and Gas Company Spills and Violations," NDRC, April 2015.

- ↑ "Colorado Oil And Gas Association Faces Resistance From Boulder Before Fracking Rulemaking Debate " John Aguilar, Boulder Daily Camera, January 3, 2013.

- ↑ Kristen Wyatt, "Colorado Air Quality Rules For Oil And Gas Drillers Gets Delayed," AP, Aug. 15, 2013.

- ↑ Amy Mall, "Fracking's Most Wanted: Lifting the Veil on Oil and Gas Company Spills and Violations," NDRC, April 2015.

- ↑ Scott Streater, "Colo. OKs groundwater sampling rule derided by industry, enviros," E&E, January 8, 2013.

- ↑ "Colorado Takes the Lead in Fracking Regulation" Kelly David Burke, Fox News, January 5, 2012.

- ↑ John Colson, "County official explains new fracking chemical rules," Post Independent, April 7, 2012.

- ↑ "Fracking Chemical Disclosure Rules," Inside Climate News chart at ProPublica, accessed April 2012.

- ↑ "Congressional Watch-Dog Warns Fracking Waste Could Threaten Drinking Water" StateImpact, Pennsylvania, July 18, 2014.

- ↑ "Fracking accident kills 1, injures 2 in Colorado" Seattle PI, November 13, 2014.

- ↑ "Ballot Initiative Challenging Oil and Gas Industry Goes to Colorado Supreme Court", Westword, March 13, 2018

- ↑ Ballotpedia: Minimum Distance Requirements for New Oil, Gas, and Fracking Projects

- ↑ Kelsey Ray, "BLM auctions drilling rights to Pawnee National Grasslands," The Colorado Independent, November 15, 2015.

- ↑ Jump up to: 61.0 61.1 61.2 John Aguilar, "Anti-fracking measures win in Lafayette, Boulder, Fort Collins," Daily Camera, Nov 5, 2013.

- ↑ "Boulder County moms rally against fracking" Amy Bounds, Daily Camera, May 13, 2013.

- ↑ Troy Hooper, "Litigation threat causes Boulder, Fort Collins to end fracking bans," The Boulder Journal, May 22, 2013.

- ↑ "All Eyes on Fort Collins Fracking Ban Vote," EcoWatch, April 22, 2013.

- ↑ Troy Hooper, "Litigation threat causes Boulder, Fort Collins to end fracking bans," The Boulder Journal, May 22, 2013.

- ↑ "Council to vote on appealing fracking ruling" Erin Udell, Coloradoan, September 23, 2014.

- ↑ "Colorado fracking battle goes to state Supreme Court, but ruling probably won't be final word" US News and World Report, December 9, 2015.

- ↑ "Judge upholds Broomfield fracking ban vote" Associated Press, February 28, 2014.

- ↑ "City of Loveland ponders water sales for oil, gas drilling" Tom Hacker, The Denver Post, April 23, 2012.

- ↑ "Petition Drive Announced to Stop Fracking in Longmont: If Successful, Longmont Would be the First Colorado City to Ban Fracking," Food & Water Watch Press Release, May 30, 2012.

- ↑ "Longmont activists start anti-fracking petition drive" Scott Rochat, Longmont Times-Call, June 8, 2012.

- ↑ Scott Rochat, "Ballot Question 300: Longmont fracking ban storms to victory," The Denver Post, Nov. 6, 2012.

- ↑ "Colorado Judge Strikes Down Longmont’s Fracking Ban in Favor of ‘State’s Interest’ in Oil and Gas" Brandon Baker, EcoWatch, July 25, 2014.

- ↑ "Groups Appeal to Protect Longmont Fracking Ban" CommonDreams, Food & Water Watch, September 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Heavyweight Response to Local Fracking Bans" Jack Healy, New York Times, January 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Fracking bans prove costly" Chris Faulkner, The Detroit News, January 7, 2015.

- ↑ "Top 10 local news stories of 2015: No. 4 — Longmont's fracking ban makes it to state Supreme Court" Karen Antonacci, Times-Call, December 27, 2015.

- ↑ "Colorado Springs group sues to allow vote on fracking ban" Ned Hunter, The Gazette, May 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Group urges fracking moratorium in Windsor" Adrian D. Garcia, The Coloradoan, October 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Fracking under way near Colorado schools" Troy Hooper, The Colorado Independent, June 5, 2012.

- ↑ Heather Hansen, "Will Colorado Transform its Water Law to Prioritize the Public Good? Colorado could amend its constitution to value public use over private and limit water diversions that negatively affect public uses," Alternet, June 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Voters in four Colorado cities may call timeout on fracking" The Denver Post, October 13, 2013.

- ↑ "Colorado Cities’ Rejection of Fracking Poses Political Test for Natural Gas Industry" Michael Wines, New York Times, November 7, 2013.

- ↑ "Hickenlooper compromise keeps oil and gas measures off Colorado ballot" Mark Jaffe, The Denver Post, August 4, 2014.

- ↑ "City removes map showing addresses of fracking opponents" Rita Brown, Energy Voice, November 1, 2015.

- ↑ "Colorado Oil and Gas Association gives $600K to fight fracking bans on Front Range ballots" Boulder Daily Camera, October 16, 2013.

- ↑ Jennifer Oldham,"Anadarko anoints 'brand ambassadors' to fight off drilling bans," Bloomberg, February 21, 2016.

- ↑ "Colorado's First Couple of Pro-Fracking Front Groups" Jesse Colema, Huffington Post, October 21, 2014.

- ↑ "Fracking Beyond The Law, Despite Industry Denials Investigation Reveals Continued Use of Diesel Fuels in Hydraulic Fracturing," The Environmental Integrity Project, August 13, 2014.

- ↑ "Fracking's Toxic Loophole Thanks to the Halliburton Loophole Hydraulic Fracturing Companies Are Injecting Chemicals More Toxic than Diesel ," The Environmental Integrity Project, October 22, 2014.

- ↑ "Air emissions near natural gas drilling sites may contribute to health problems," News Med, March 19, 2012.

- ↑ Lisa Sumi, "Inadequate enforcement means current Colorado oil and gas development is irresponsible," Earthworks Report, March 2012.

Related SourceWatch articles

Click on the map below for state-by-state information on fracking:

External links

- FracTracker

- Boulder/Denver community radio station KGNU fracking coverage including ballot items, state capitol/legislature, county commission

External Articles

- John Colson, "Former gas industry ‘water handler' now a whistleblower," Colorado Post Independent, March 10, 2012.

| This article is a stub. You can help by expanding it. |